The mother-daughter relationship is primal and one of the most talked about in the media was that of Teri and Brooke Shields. It’s also a topic that Brooke has always shied away from, until now. In her latest literary project, Brooke explores her relationship with her mother as well as with her own two daughters.

When I met with Brooke at Soho House, we discussed her upcoming book. “The reason I wanted to write the book is not to say: ‘You didn’t understand: She was the best mother in the world.’ I’m not holding her up on a pedestal, nor am I painting her as a villain or a victim. It’s to say that the mother-daughter relationship is so archetypal. There is something in that: It is our primary relationship. We are born of it. There is something to be said when looking at the complexity of it,” said Brooke.

In the eyes of the public, Brooke’s relationship with her mother was quite complex. Many say that Teri was the first of what is now a subset of mothers known as the momager, or what used to be called the stage-mom. In 1977, a New York Magazine cover story claimed that Teri had sold Brooke into Hollywood slavery. But what exactly did this mean? When I asked Brooke about her childhood with her mother and the media push-back, she replied, “You know what’s so funny about a lot of the things that they were pushing back on her for? Those things were the least of my worries. I was exploited? I was in school full time. Seriously, the opportunities I had: the trips I got to go on; the people I got to meet; the car I got to buy; and the house I got to buy. I wasn’t worried about what they were saying. That was not the issue. I was a virgin, so how could I care about people saying things about my virginity, pornography, or anything else?” Brooke continued to talk about how important education was to her mother and how Teri allowed Brooke only a taste of the wilder side of life. “We would go to Studio 54 together, but I would be home by eleven.” If one compares Teri Shields to some of today’s momagers who are infamous for partaking in all-night ragers with their child-starlets, Teri could arguably seem straitlaced

by comparison.

It’s important to note that we live in a society that has traditionally peddled an unrealistic image of the saintly mother: Hallmark cards, Lifetime specials, and Mother’s Day all focus on a mother’s selflessness and generosity. There is no recognition of the reality of a mother’s multifaceted personality. Is she not allowed to be human? Can’t someone who is essentially selfless also have moments of self-interest? The aggregate press about Brooke’s mother isn’t flattering. The main focus of attack was always Brooke’s supposed objectification by her mother. But is it fair to have expected Teri — who lived in a world that objectified women and celebrated them mainly for their beauty — to have existed apart from these prevailing social forces, at a time when feminism was only starting to blossom? Perhaps the most controversial interview was in the early 1980s, when Teri told the TV interviewer Bill Boggs that she had always been aware of her daughter’s beauty and thought it best to take advantage of it. Teri’s acknowledgement that her daughter had a sexy-innocent appeal has been recycled in the majority of articles that discuss her life. It’s unfortunate that a musing during an interview, a few seconds of Teri’s life, turned out to define her. We live in a hypocritical society that gladly bought into and celebrated Brooke, yet turned around and tore her mother down. Much might be said about the Boggs interview, or other times that Teri had a similar message, but perhaps the most telling clue about who was “at fault” — Teri or society — is to see where we are now as a culture.

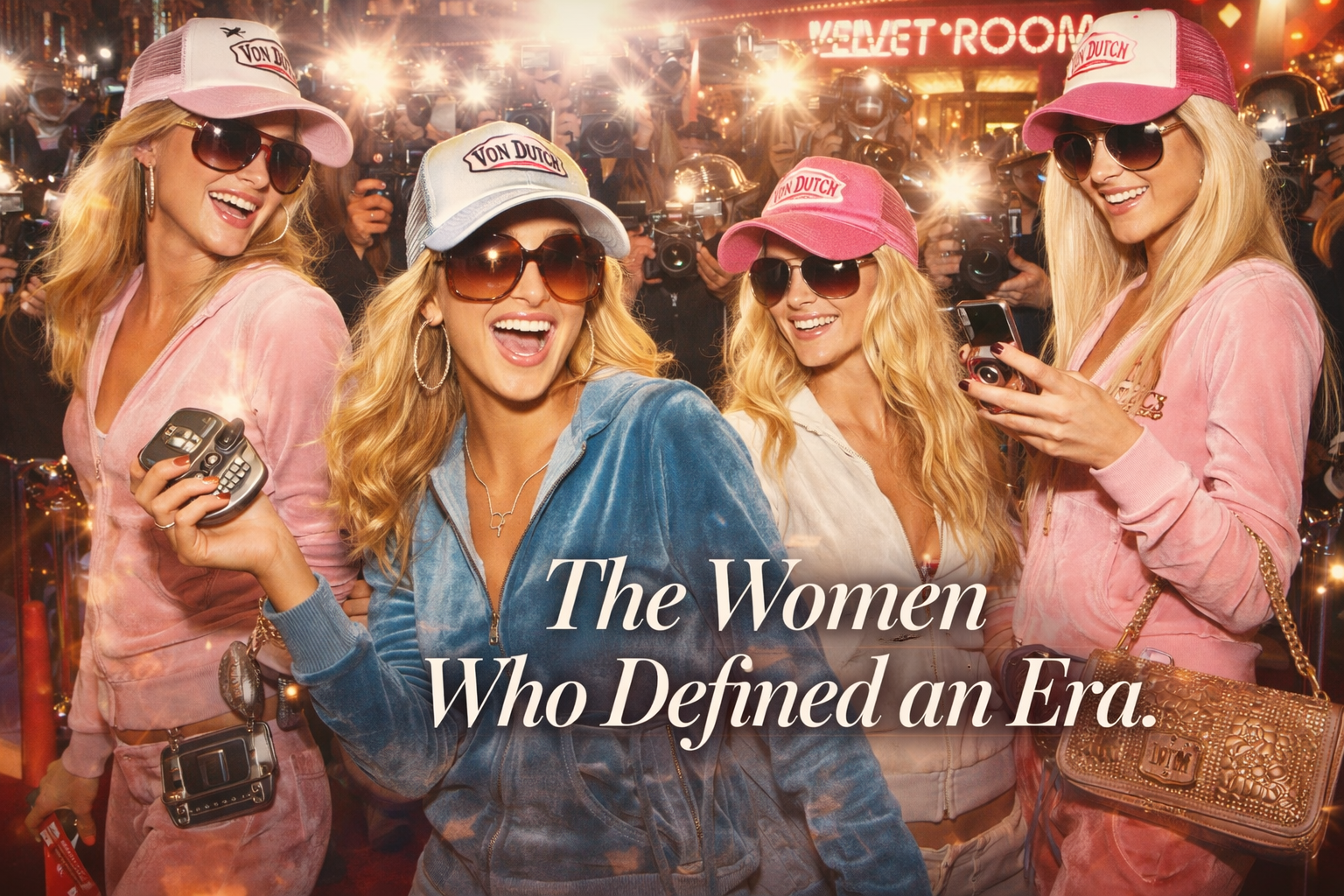

Historians know that the effects of a president’s choices cannot be known for years, perhaps decades. If society were a person, would its evolution have a tale to tell? Mothers and daughters today look much different from when Brooke was growing up. Young girls are sexier than ever before. In fact, the pornification of young women’s fashion is a highly discussed topic. Likewise, the creation of the “cougar” has placed the sexual spotlight on mothers. What today’s society believes about a young women’s body is pretty clear. Does the evolution of today’s world into a culture that promotes nymphets reveal anything about the treatment of Teri Shields? Perhaps Teri was a product of social forces that have now just fully materialized.

In her book, Brooke also discusses what it’s like to be a mother herself and her relationships with her own two daughters. About her own parenting style, Brooke said: “I’ve learned from my daughters about the power of asking rather than just dictating. Because the thing is, I can’t dictate to my children as if I’ve been in their shoes. I’m not them. I’ve never been their age in this era. They can’t possibly identify with my circumstances. I’m basically trying to teach strangers. I don’t know what it feels like to be them, and so I have to ask questions to find out.” She compared and contrasted her roles as mother and daughter: “I never would have questioned my mother about anything. She could have had my ear pierced way over here and a completely mismatched other piercing, and I would have been, like, ‘Yeah I get it; it looks pretty even to me.’ I see that now, you know. She could have said this table was white and I would have found a white speck somewhere in there. You know, I was so attached to my mother, and my daughters are not like that with me at all, because I think I am doing a healthier job with them, hopefully.” What Brooke said reminded me of what Erich Fromm wrote: “The mother-child relationship is paradoxical and, in a sense, tragic. It requires the most intense love on the mother’s side, yet this very love must help the child grow away from the mother, and to become fully independent.”

Could the mother-daughter bond be the most powerful connection in a woman’s life? A mother is a living definition of womanhood; she models how a woman views the world and how a woman should move through this world. In a culture of beauty magazines and movies, women’s bodies are not their own. Others tell females how they should look and what they ought to do with their bodies. Maybe older and younger generations of women can arrive at an understanding, one that acknowledges how both have looked into the same judgmental mirror, traveled down the same roads, shared similar heartaches and life challenges. Maybe there can be a discussion through the mother-daughter lens that focuses on the regard of women now and in the past. This will help us to better understand our mothers and ourselves and enable us to forge a new way with our daughters and granddaughters. Perhaps then society will begin to change its views.

“The problem is it’s not just about respecting our parents; it’s about learning how to respect ourselves. This is not what we are teaching our young,” Brooke said seriously. But in the next breath, she smiled and added: “Listen, I don’t have all the answers. I have one very rebellious child and one very different rebellious child. I’m still learning from them while teaching them at the same time.”

Parenting seems to have many contrasts. In the paradoxical world that is current-day America, Brooke Shields — famous for being a daughter — is now a mother herself. Brooke’s upcoming book will be important, much like her brave exploration of postpartum depression, because it won’t only examine parts of her relationship with her mother and her daughters, it will examine the mother-daughter connection, that fundamental building block of every woman’s formation. Brooke said about her exploration of this bond: “The ambiguity is the closest thing to truth that I’ve found in analyzing my life with my mother. The sooner I was able to sort of give into that, the more committed I was to writing about it.”

The one thing that I’m very sure of: I’m truly looking forward to reading Brooke’s upcoming work.