The $1 Postcard That Started Everything

The mythology begins in 1979 at a restaurant in SoHo. Basquiat, then nineteen and homeless, approached Warhol’s table and tried to sell him a postcard. Warhol bought it for a dollar. The transaction lasted seconds. Neither remembered it particularly well.

The relationship that mattered started three years later on October 4, 1982. Swiss art dealer Bruno Bischofberger, who represented both artists, arranged a lunch meeting at Warhol’s Factory. Bischofberger had a proposal: collaborative paintings between three artists. He wanted Warhol, Basquiat, and Italian painter Francesco Clemente to mail canvases back and forth, each adding their mark.

Warhol was skeptical. His diary entry from that day reveals casual condescension toward the young artist Bischofberger brought along. He described Basquiat as the kid who used to sit on sidewalks painting T-shirts, noting he used to give him ten dollars here and there. He questioned whether Basquiat was really an important artist.

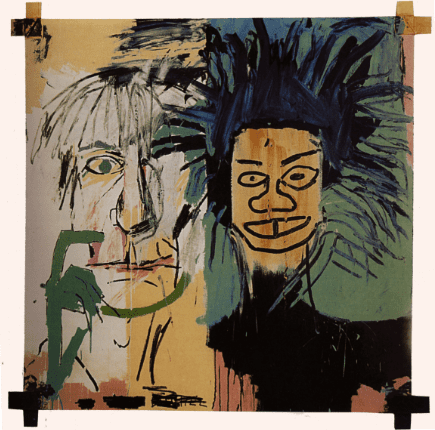

Then something unexpected happened. Warhol took a Polaroid of himself and Basquiat together. Basquiat grabbed the photo, skipped lunch, and raced back to his studio. Within two hours, his assistant delivered a large canvas to the Factory. Still wet. A double portrait titled Dos Cabezas—two heads, rendered in Basquiat’s jagged, electric style.

Warhol’s skepticism evaporated. He told Bischofberger he was jealous. The kid was faster than him.

What Each Artist Needed From the Other

Their collaboration wasn’t accidental. Each saw in the other something they lacked.

Warhol, by 1982, had become what he most feared: predictable. His silkscreen technique, once revolutionary, had calcified into formula. Critics dismissed his commissioned celebrity portraits as expensive wallpaper. He needed disruption. He needed someone to make him paint by hand again.

Basquiat needed credibility. He’d risen from Brooklyn graffiti artist to gallery sensation in barely two years. At twenty-one, he became the youngest artist ever to exhibit at Documenta. At twenty-two, the youngest at the Whitney Biennial. But velocity breeds suspicion. Critics wondered if he was a genuine talent or a market creation. Warhol’s blessing—the imprimatur of an artist who’d survived three decades of art world scrutiny—offered legitimacy.

Artist Ronny Cutrone, who worked at the Factory, watched their dynamic closely. He called it a crazy art-world marriage between odd couples. He observed that the relationship was symbiotic: Basquiat thought he needed Warhol’s fame and Warhol thought he needed Basquiat’s new blood. Basquiat gave Warhol a rebellious image.

The symbiosis worked. Both artists changed.

How They Actually Painted Together

The collaborative process defied conventional studio practice. Warhol typically started. He’d project a recognizable image onto canvas—a corporate logo, a newspaper headline, the Olympic rings—and trace or silkscreen it. Then Basquiat would arrive and, as he put it, deface it.

Basquiat pushed for iteration. He tried to get Warhol to do at least two things on each canvas instead of just one hit. Warhol resisted but often relented. Their back-and-forth created layered palimpsests: Warhol’s cool mechanical precision buried under Basquiat’s anarchic energy, then partially excavated, then buried again.

Keith Haring, their downtown contemporary, witnessed them working together and described it as a physical conversation happening in paint instead of words. He saw humor, snide remarks, profound realizations, and simple chit-chat all rendered in paint and brushes. Each inspired the other to outdo the next.

The collaborative works fell into distinct categories. Some featured Warhol’s hand-painted logos—Arm and Hammer, Paramount, General Electric—which Basquiat would annotate and subvert. Others started from Warhol’s simple motifs: dogs, fruit, household appliances. The most complex pieces became nearly impossible to attribute. Warhol noted with satisfaction that the paintings they did together were better when you couldn’t tell who did what.

Between 1983 and 1985, they produced approximately 160 joint works. The output was staggering.

The Daily Rituals Behind the Paintings

Their collaboration extended beyond canvas. Warhol, obsessive documentarian that he was, photographed nearly every interaction. His diaries reveal the texture of their friendship: gym sessions, shopping trips, gallery dinners, manicures.

They worked out together regularly. Warhol, ever image-conscious, noted in his diary entries when Basquiat would join him and his trainer Lidija for workouts. One entry from August 1983 described meeting Basquiat at the gym, observing that he was in love with Paige Powell, an editor at Interview Magazine who would become one of Basquiat’s girlfriends.

The physical intimacy of their friendship fueled speculation. Warhol photographed Basquiat shirtless, in briefs, in a jockstrap. He called him cute and adorable in diary entries. But those who knew them described the relationship as platonic—an intense creative bond between two profoundly different personalities.

Warhol became Basquiat’s landlord in 1983, renting him the loft at 57 Great Jones Street where Basquiat would eventually die five years later. The rent was nominal—essentially a dollar a year, guaranteed by Bischofberger. It bound them together practically as well as artistically.

The 1985 Exhibition That Destroyed Everything

In September 1985, Tony Shafrazi Gallery mounted the first major exhibition of their collaborative works. The boxing-gloves poster promised spectacle. The critical response delivered demolition.

Vivien Raynor’s review in The New York Times set the tone. She wrote that the previous year she had noted Basquiat had a chance of becoming a very good painter provided he didn’t succumb to the forces that would make him an art world mascot. Those forces, her review declared, had prevailed. The collaboration looked like one of Warhol’s manipulations, with Basquiat cast as an all too willing accessory.

The word “mascot” hit like a bullet. It echoed every racist dismissal Basquiat had endured—the critics who called his work primitive, the collectors who brought fried chicken to his studio, the galleries that treated him as exotic entertainment rather than serious artist.

Hilton Kramer piled on in the same publication. Not a single painting sold before the show closed.

Basquiat was shattered. According to friends who knew him, these reviews marked the beginning of the end—a downward spiral from which he never recovered. He stopped visiting the Factory for their regular painting sessions. When asked if he was upset about the “mascot” remark, he claimed he wasn’t, but his behavior suggested otherwise.

Warhol sensed the distancing. A diary entry captured his awareness that Basquiat hadn’t called in a month. He wrote that the younger artist kept calling him and then not calling him.

The Complications of Friendship

Warhol’s diaries reveal a relationship more fraught than the mythology suggests. He described Basquiat as so complicated that you never knew what mood he was in or where he stood. He noted Basquiat’s paranoid accusations that Warhol was just using him, followed by guilt about the paranoia.

Basquiat’s drug use strained their bond. Warhol documented Paige Powell coming to him in tears, begging him to do something about Basquiat’s heroin problem. Warhol’s response was helpless: what could he do?

When Basquiat came to Warhol and said he was depressed, that he was going to kill himself, Warhol laughed and said it was just because he hadn’t slept for four days. The moment captured something essential about both men: Basquiat’s genuine fragility masked as performance, Warhol’s protective detachment that sometimes looked like cruelty.

They fell out completely after the Shafrazi disaster. Basquiat fled New York, hurt and wanting distance between their works. It became embarrassing for them to be seen together.

The Death That Made Everything Worse

Andy Warhol died unexpectedly on February 22, 1987, following routine gallbladder surgery. He was fifty-eight. Cardiac arrhythmia, the official cause. The art world reeled.

Basquiat, who had distanced himself from Warhol for nearly two years, unraveled completely. Fred Brathwaite, the artist known as Fab 5 Freddy, observed that Warhol’s death put Basquiat into total crisis. He couldn’t even talk.

Basquiat painted Gravestone as a memorial. He became reclusive. His heroin consumption accelerated to what some sources estimated at one hundred bags per day. Eighteen months after Warhol’s death, Basquiat was dead at twenty-seven.

The collaborative works they’d made together—universally dismissed in 1985—entered a strange limbo. Neither artist lived to see their rehabilitation.

The Critical Reappraisal Nobody Expected

For decades, the Warhol-Basquiat collaborations remained art market orphans. Works by either artist individually commanded premium prices. Their joint productions underperformed consistently.

The turning point came in 2023. Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris mounted Basquiat x Warhol: Painting Four Hands—the most comprehensive exhibition of their collaborative works ever assembled. Seventy joint canvases plus over two hundred related pieces filled four floors of Frank Gehry’s spectacular building. The show drew nearly 700,000 visitors.

A version traveled to the Brant Foundation in New York later that year. Peter Brant, mega-collector and longtime champion of both artists, had curated solo shows of each at his East Village space. Now he reunited them.

The exhibitions forced critics to reconsider. What had looked like manipulation in 1985 now appeared as genuine creative exchange. What had seemed like exploitation now read as mutual transformation. Sotheby’s chairman of contemporary art, Grégoire Billault, declared the collaborations undoubtedly the most important artistic collaboration of the twentieth century.

What Collectors Are Paying Now

The market responded accordingly. In May 2024, Sotheby’s offered Untitled (1984)—a monumental canvas nearly ten feet by thirteen feet—as the highlight of their contemporary evening sale. Created using the Surrealist technique of “exquisite corpse,” it featured Warhol’s baseball mitts and corporate logos overwritten by Basquiat’s totemic figures and color fields.

The hammer fell at $19.4 million. A new auction record for their collaborative series, seventy percent above the previous high.

Individual works by each artist still command more. Warhol’s record stands at $195 million. Basquiat’s reached $110.5 million in 2017. But the collaboration premium is accelerating. Works that couldn’t sell in 1985 now anchor evening auctions.

The collector calculus has shifted. A Basquiat signals cultural sophistication. A Warhol signals Pop Art fluency. Owning both together—the only documentation of their creative partnership—signals something rarer: access to a moment that can’t be replicated.

What the Partnership Means for Art Collectors Today

The Warhol-Basquiat rehabilitation offers lessons for sophisticated collectors. Critical consensus at any moment captures fashion, not value. The works savaged in 1985 were the same works celebrated in 2023. Only perception changed.

The collaboration also demonstrates what advisors like Isabella del Frate Rayburn have long understood: provenance as narrative. A collaborative Warhol-Basquiat carries stories that single-artist works cannot. The boxing-gloves photograph. The gym sessions. The mascot scandal. The deaths eighteen months apart. These stories compound value over time.

Their estates continue to collaborate posthumously through licensing—Basquiat crowns appear on Crocs and Tiffany campaigns, Warhol’s imagery fuels countless partnerships. But the original collaborative paintings remain finite. Approximately 160 exist. Each major sale removes one from circulation.

For collectors in markets like the Hamptons art scene, understanding this partnership provides essential context. Basquiat and Warhol aren’t just individual artists. They’re a single story about ambition, exploitation, genuine connection, and the decades it sometimes takes for the art world to understand what it witnessed.

That story, it turns out, is worth $19 million and counting.