The House That Refuses to Be Bought

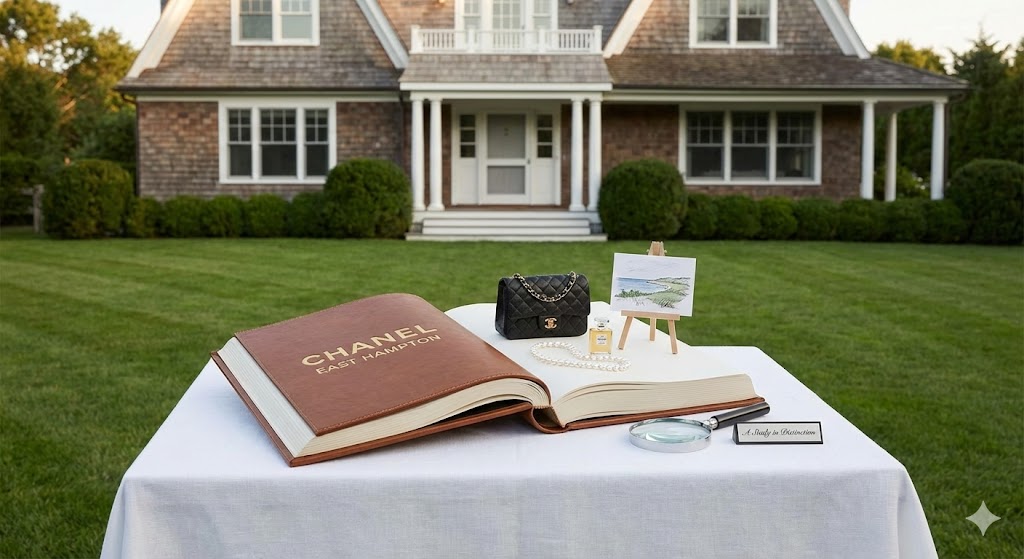

Standing outside 28 Newtown Lane, a woman does not look at the price tags. She already knows. Before her, the gray-shingled building could be any well-kept Hamptons cottage, save for the black-and-white palette visible through the windows and the gold letters spelling a name that needs no introduction. This is the Chanel East Hampton seasonal boutique—open from Memorial Day through Labor Day—and furthermore, it represents something far more interesting than retail: the physical manifestation of a century-old question about who gets to define taste.

Inside, a Chanel 2.55 bag sits in quilted leather splendor, priced at $11,300. In 2010, that same bag cost $3,700. Consequently, the math is brutal: a 95% increase in just five years. According to Bain & Company’s 2024 luxury report, this aggressive pricing has shrunk the global customer base by 50 million people over the past two years. Yet the woman does not hesitate. She is not buying a bag. Instead, she is buying something far more expensive: entry into a world that doesn’t need her money.

What happens at Chanel East Hampton is not commerce. It is conversion.

Pierre Bourdieu, the French sociologist who spent his career dissecting how the ruling classes maintain power through taste, would recognize this transaction instantly. Indeed, what unfolds at Chanel East Hampton is not commerce but conversion—the exchange of economic capital for something more durable, more inheritable, and infinitely more difficult to acquire: cultural legitimacy.

The Genesis: From Orphanage to Empire

Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel was born in Saumur, France, on August 19, 1883. When her mother died, she was only eleven. Her father subsequently abandoned her at a Cistercian convent orphanage called Aubazine, where she would spend six years learning to sew in monastic silence. Black and white uniforms surrounded her daily. Bare walls defined her world. Moreover, the message was unmistakable: she was nobody, destined for nothing.

This origin story matters because every element of Chanel’s design vocabulary emerged from these years of imposed austerity. Consider the black, the white, the clean lines, the absence of ornament. Therefore, what looks like sophisticated minimalism is actually the aesthetic of institutional poverty, transformed into its opposite through sheer force of will. Even the burgundy lining of her iconic bags—still used today—references the convent uniforms she wore as a child.

In 1910, with financial backing from her lover Arthur “Boy” Capel, Chanel opened a millinery shop at 21 rue Cambon in Paris. Initially, she was selling hats to aristocratic women who had never worked a day in their lives. Soon, however, she began selling them something more revolutionary: clothes that allowed them to move freely. Jersey fabric, previously reserved for men’s underwear, became haute couture. Loose silhouettes eliminated the corset entirely. Fashion suddenly implied the wearer had something better to do than simply be looked at.

American Vogue, in October 1926, published a sketch of her little black dress and called it “the Ford of fashion.” Like the Model T, Chanel’s designs democratized access while simultaneously offering the uniform of elegance to anyone who understood the code. Nevertheless, this apparent democracy concealed a deeper truth. While the dress was simple, knowing it should be simple required an entirely different education—one money alone could not purchase.

The Mythology Machine

Coco Chanel understood something her contemporaries did not: the best luxury branding erases its own origins. Throughout her life, she told multiple versions of her story. She claimed “Coco” came from a cabaret song. Alternatively, she said it derived from her father’s pet name. Sometimes she implied it referenced the French word for “kept woman.” Each version served the same purpose—the ambiguity transformed poverty into mystery, abandonment into independence, shame into style.

This mythology machine still operates today with remarkable efficiency. Currently, the Chanel website describes Gabrielle as someone who “lived her life as she alone intended.” The orphanage becomes “an education in rigor.” The wealthy lovers who funded her business become “muses.” Accordingly, the entire enterprise of rebranding deprivation as distinction continues, season after season, collection after collection, even at 28 Newtown Lane.

Chanel’s Four Capitals: Decoding Luxury’s Hidden Currency

Economic Capital

Chanel ranks as the second-largest luxury brand in the world, generating $18.7 billion in revenue in 2024. Unlike its competitors at LVMH or Kering, however, it remains privately held. The Wertheimer brothers—Alain and Gérard—own it entirely through a holding company based in London. Their combined net worth exceeds $100 billion, and in the last three years alone, Chanel paid $12.4 billion in dividends to the family.

Examining the price architecture reveals its own story. Entry-level accessories begin around $1,000, while the Classic Medium Flap bag now retails for $11,300—up from $5,800 in 2019. Meanwhile, haute couture gowns can exceed $100,000. Consequently, the message is architectural: there is always another level you cannot afford, another room you cannot enter.

This aggressive price elevation serves multiple functions. Obviously, it increases margins. But it also shrinks the customer base by design—a feature, not a bug. Furthermore, as Sotheby’s notes, it transforms products into investments. A vintage Classic Flap from the 1990s that cost $1,200 now fetches over $6,000 on the secondary market. Thus, the bag becomes a financial instrument, and financial instruments require financial literacy to properly evaluate.

Cultural Capital

What must you know to properly consume Chanel? Answering this question reveals the brand’s true exclusivity mechanism—one far more powerful than price alone.

First, you must know that the 2.55 bag, named for its February 1955 debut, features a “Mademoiselle lock”—so called because Coco never married. Additionally, you must know the burgundy lining references her convent uniform, while the chain strap was inspired by the key chains worn by the nuns who raised her. You must also recognize that Karl Lagerfeld’s “Classic Flap,” with its interlocking CC clasp, is a different bag entirely from the original 2.55—a distinction lost on the uninitiated.

Similarly, you must know that Chanel No. 5, created by perfumer Ernest Beaux in 1921, was revolutionary because it smelled “like a woman, not like a rose.” You should understand the aldehydes—synthetic compounds that gave the fragrance its sparkling, almost soapy quality. Certainly, you must know that Marilyn Monroe claimed to wear nothing else to bed. And ideally, you would know that Beaux presented Coco with samples numbered 1 through 5 and 20 through 24, and that she chose number 5 because she presented her collections on the fifth day of the fifth month.

This knowledge cannot be purchased directly. Instead, it must be accumulated through exposure, through reading, through the kind of leisure that only money or education provides. Consequently, cultural capital functions as a sorting mechanism far more effective than price alone—separating those who merely own Chanel from those who truly understand it.

Social Capital

Purchasing Chanel means joining a specific network. In the Hamptons, this network operates on visual recognition. Consider the quilted pattern, the interlocking Cs, the two-tone slingback—these are membership cards to an invisible club whose rules are never explicitly stated.

Examining the brand’s ambassador roster reveals a map of legitimate celebrity: Penélope Cruz, Brad Pitt, Lily-Rose Depp, Jennie Kim. Notably, these are not influencers but established cultural producers with their own claims to distinction. Unlike brands that court viral attention, Chanel does not sponsor the aspirational. Rather, it consecrates the already-consecrated.

In the Hamptons specifically, Chanel ownership signals something precise. It says: I have been wealthy long enough to know that logo-heavy design is vulgar. It says: I understand the difference between new money and old money aesthetics. It says: I belong to a class that does not need to prove itself. Therefore, the social capital at stake is not merely access but identity—the ability to be recognized by one’s own kind without speaking a word.

Symbolic Capital

What does carrying Chanel say about you? Although the answer has shifted over the century, certain constants remain embedded in the brand’s DNA.

Above all, Chanel confers the prestige of knowing better. Its aesthetic has always been about refusal—the refusal of ornament, the refusal of effort, the refusal to try too hard. This is what Bourdieu called “legitimate taste”: the taste that does not need to justify itself because it has been sanctioned by the cultural authorities who matter.

In the competitive field of Hamptons luxury, Chanel occupies a specific position. It is not as exclusive as Hermès, which rations its Birkins through an elaborate game of “purchase history.” Nor is it as flashy as Gucci or Louis Vuitton. Instead, Chanel represents the precise midpoint where accessibility meets authenticity. Thus, the woman with the Chanel bag has demonstrated she can afford better than Coach but has chosen not to perform the grotesque spectacle of Hermès supplication.

This positioning resolves a fundamental anxiety for its customers: the fear that wealth is visible but taste is not. Chanel promises to close that gap. Essentially, it promises that money can, in fact, buy class—provided you know which class to buy.

Why Chanel Chose the Hamptons—And What It Reveals

Opening a seasonal boutique at Chanel East Hampton in 2022 was not arbitrary. Rather, the Hamptons represent something specific in the American luxury landscape: wealth that wishes to appear effortless. Unlike Palm Beach’s performative glamour or Aspen’s athletic showmanship, the Hamptons aesthetic prizes restraint. Old money families who have summered here for generations favor understated elegance over obvious logos.

This environment perfectly mirrors Chanel’s brand positioning. The 2,500-square-foot boutique on Newtown Lane offers ready-to-wear, handbags, fine jewelry, watches, and beauty products. However, its very existence sends a message beyond merchandise. While other luxury brands maintain year-round presence, Chanel’s seasonal schedule—Memorial Day through Labor Day—reinforces exclusivity. You cannot buy Chanel East Hampton in January because Chanel decides when East Hampton needs Chanel.

The Competitive Landscape

Hermès, in Southampton, offers the ultimate in restricted access through its famously rationed handbags. Gucci and Valentino compete on creative energy, appealing to those who want to be seen as fashion-forward rather than merely wealthy. By contrast, Chanel positions itself differently. It says: we are more accessible than Hermès, more serious than Gucci, more authentic than Louis Vuitton.

The tweed suits that made Coco famous still appear each season, largely unchanged. The 2.55 bag has barely evolved in seventy years. Moreover, the brand does not chase trends because it defines them. This positioning serves both old money and new money—but differently. Old money appreciates the lack of obvious branding, the quiet codes, the heritage. Meanwhile, new money appreciates the legibility, the recognizable status markers, the entry into a world their parents could not access. The same product, worn by different customers, means different things. Ultimately, this ambiguity is the source of Chanel’s enduring power.

The Investment: Cultural Arbitrage or Conspicuous Consumption?

The Chanel East Hampton seasonal boutique is open daily from 11 AM to 6 PM, Sundays from noon to 6 PM. Located at 28 Newtown Lane, East Hampton, NY 11937, it carries most major product categories, with particular emphasis on beach-appropriate ready-to-wear and the fine jewelry collection.

What type of customer does this store serve best? Specifically, the answer is someone wealthy enough to afford the prices, educated enough to appreciate the codes, and confident enough to wear the products without explanation. This demographic is narrower than Chanel’s economic accessibility might suggest, because the cultural literacy required for meaningful engagement is substantial.

You must understand why the little black dress matters historically. You must know the significance of pearls, of camellias, of the number 5. Furthermore, you must recognize that what looks simple required enormous effort to simplify. Finally, you must believe—or at least convincingly perform belief—that these distinctions matter in a world that often pretends they do not.

The woman leaving the Chanel East Hampton boutique carries more than a shopping bag. She carries 114 years of mythology, the accumulated cultural capital of one of fashion’s most deliberate constructions, and entry—however temporary—into a world that values knowing over having. What is Chanel really selling in the Hamptons? The answer has not changed since 1910: the resolution of a specifically modern anxiety. Not whether you have money. Whether you deserve it.

Sources & Further Reading

For additional background on Chanel’s history and market position, consult Business of Fashion, Bain & Company’s luxury reports, and Sotheby’s fashion archives. For deeper exploration of Bourdieu’s capital theory, see Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Harvard University Press).