The wrecking balls started swinging at 6 PM on January 7, 1985. By midnight, four buildings on West 44th Street had been reduced to rubble.

Harry Macklowe had ordered the demolition without permits, without disconnecting the gas lines, and without any legal authority whatsoever. The city’s moratorium on destroying single-room occupancy hotels was set to take effect in 36 hours. So Macklowe hired a construction crew with ties to the Genovese and Gambino crime families and told them to work through the night. When dawn broke over Times Square, nothing remained but dust and controversy. The contractor would later be assassinated in a mob-style hit. Meanwhile, Macklowe would pay a $2 million fine—the largest environmental penalty in New York City history at the time—and simply keep building.

Harry Macklowe’s net worth currently sits at approximately $2 billion. At 88 years old, he remains actively acquiring properties, most recently purchasing 809 Madison Avenue in September 2025 for $49 million. The college dropout who shoveled snow for 15 cents an hour became the man who changed Manhattan’s skyline forever. The question isn’t how he made his fortune. It’s what that fortune reveals about the price of ambition.

What Is Harry Macklowe’s Net Worth in 2025?

Harry Macklowe’s net worth is estimated at $2 billion in 2025, though the figure has fluctuated dramatically throughout his career. Forbes once estimated his wealth at $2 billion in 2007, but financial reversals dropped him from the billionaires list entirely by 2008. Following his contentious $2 billion divorce from Linda Burg Macklowe in 2018, both parties emerged with estimated fortunes between $450 million and $550 million. However, his continued development projects and real estate holdings have rebuilt that wealth substantially.

The net worth calculation becomes complicated because Macklowe Properties operates with tremendous leverage. During his 2018 divorce trial, Macklowe’s own legal team argued his net worth was negative $400 million due to deferred capital gains. His ex-wife’s team countered that he was hiding assets. Consequently, a judge ordered their $922 million art collection sold at auction and split down the middle. The collection, featuring works by Rothko, Warhol, and Giacometti, became the most valuable private collection ever sold at auction.

The Wound: A Garment Executive’s Son With Something to Prove

Harry Macklowe was born in 1937 to a Jewish family in Westchester County, New York. His father worked as a garment executive—comfortable but hardly wealthy. Young Harry grew up in New Rochelle, attending public school and developing early hustler instincts. “My first job was shoveling snow for 15 cents an hour,” Macklowe later recalled at an event in the GM Building he once owned. “And after that, it was caddying at the Wykagyl Country Club in the summers.”

Those early experiences watching wealthy club members planted something in him. After graduating from New Rochelle High School in 1955, Macklowe bounced between the University of Alabama, New York University, and the School of Visual Arts before dropping out entirely in 1960. Academia held no appeal. Instead, he married Linda Burg, a doctor’s daughter working as an editorial assistant at Doubleday, and moved into a garden apartment in Brooklyn.

The Brooklyn Landlord Who Changed Everything

That Brooklyn apartment would prove more educational than any university. The landlord ran a brownstone renovation business, and 21-year-old Harry watched closely. He developed a fascination with the mechanics of real estate—how buildings could be bought, improved, and sold for profit. The landlord recognized something in Macklowe and encouraged him to get his real estate broker’s license. By 1960, Harry had transitioned from tenant to broker, working briefly in advertising before landing at Julian Studley’s commercial brokerage firm, where he leased space in the Pan Am Building.

In 1964, everything changed. Macklowe acquired his first office building on East 28th Street for $27,500. He would eventually sell it for $12 million. The garment executive’s son had found his calling. Real estate wasn’t just about buildings. It was about vision, leverage, and the willingness to bet everything on what you could see that others couldn’t.

The Chip: Rules Are for People Without Vision

Macklowe’s rise through New York real estate was marked by an almost pathological impatience with obstacles. Where other developers saw regulations, he saw inconveniences to be circumvented. Where others saw historic buildings, he saw impediments to progress. This worldview would make him both spectacularly successful and perpetually controversial.

The midnight demolition of 1985 crystallized this approach. Macklowe wanted to build a luxury hotel on West 44th Street near Times Square. Four buildings stood in his way, including two single-room occupancy hotels housing low-income tenants. A city moratorium on SRO demolitions loomed. Rather than accept delay, Macklowe paid contractor Eddie Garofalo $380,000 to demolish the buildings overnight—without permits, without disconnecting utilities, without even finalizing the property purchase from seller Sol Goldman.

The resulting investigation revealed breathtaking recklessness. Gas lines remained connected during demolition, risking explosion. Workers operated without proper safety measures. The judge who later ruled on damages noted that “nobody was hurt and other property and people were not damaged is purely fortuitous.” Garofalo was indicted and later assassinated in 1990 in what police described as a mob-style killing. Macklowe paid the $2 million fine, waited out a four-year development ban, and eventually built the Hotel Macklowe on the site anyway.

The Rise: From Midnight Demolition to Billionaires’ Row

Despite—or perhaps because of—his willingness to break rules, Macklowe’s career trajectory proved extraordinary. Throughout the 1980s, he developed sleek modernist buildings that architectural critics alternately praised and condemned. Metropolitan Tower drew particular fire, with New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger calling it “the least respectful of the architectural traditions” in its vicinity. Macklowe dismissed the criticism: “Just because I’m a developer and we do the architecture ourselves.”

The early 1990s brought financial hardship. Economic recession forced Macklowe to surrender Hotel Macklowe to lenders. Plans to take the company public collapsed amid the Japanese financial crisis. Yet he never fully retreated, developing smaller projects with his son William until the opportunity for comeback arrived.

The GM Building and the Apple Cube

That comeback came in 2003 when Macklowe purchased the General Motors Building for a record $1.4 billion. The acquisition demonstrated both his audacity and his genius for value creation. Macklowe personally pitched Apple CEO Steve Jobs on building a subterranean retail store beneath the building’s plaza. Jobs proposed the entrance be a 32-foot glass cube—now one of Manhattan’s most photographed landmarks. The Apple Store became outrageously profitable, and the building’s value doubled.

Emboldened by success, Macklowe made his boldest gamble yet. In February 2007, at the absolute peak of the real estate market, he purchased seven Manhattan skyscrapers from the Blackstone Group for $6.8 billion. The deal structure was breathtaking: $50 million of his own money, with $7 billion in short-term loans from Deutsche Bank and Fortress Investment Group due in one year.

Then the financial crisis hit. Macklowe couldn’t refinance. In early 2008, he lost all seven buildings, including the GM Building he had acquired just five years earlier. The properties were sold to Boston Properties and Goldman Sachs for $4 billion. His son William blamed him publicly for mismanaging the family business. His wife Linda sided with their son. The family fractured along with the empire.

432 Park Avenue: The Tower That Defined His Legacy

Most developers would have retreated after such a catastrophic loss. Macklowe doubled down. He demolished the historic Drake Hotel to make way for 432 Park Avenue, a 1,396-foot residential tower that would become the tallest residential building in the Western Hemisphere upon completion in 2015. Designed by Rafael Viñoly, the pencil-thin structure featured 104 ultra-luxury apartments with panoramic views commanding prices up to $95 million.

The building drew immediate controversy. Critics attacked its “ugly” design, accusing Macklowe of ruining the skyline. Tony Malkin, CEO of Empire State Realty Trust, called it “medieval” because it reminded him of towers built in the Middle Ages to protect and isolate the wealthy. Residents later complained of structural deficiencies, leaky pipes, and excessive noise when wind howled through the building’s distinctive grid pattern.

None of this bothered Macklowe. He was busy planning his next project—and his next marriage.

The Tell: The $2 Billion Divorce and the 42-Foot Billboard

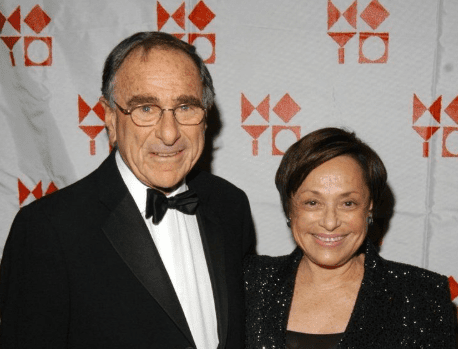

In 2016, after 57 years of marriage, Linda Macklowe filed for divorce. Harry had left her for Patricia Landeau, the honorary president of the French Friends of the Israel Museum. What followed was the most expensive and contentious divorce in New York history.

The 14-week trial in 2018 became tabloid heaven. Harry’s lawyers argued his companies “lose money every year” and pegged his net worth at negative $400 million. Linda’s team presented evidence of vast hidden wealth. Neither side could agree on the value of their contemporary art collection, featuring masterworks by Rothko, Warhol, Pollock, and Giacometti. Judge Laura Drager ultimately ordered the entire collection sold at auction.

The Sotheby’s sale in 2021-2022 shattered records. The first half brought $676 million. The second half pushed the total to $922 million, making it the most valuable private art collection ever sold at auction. “I never thought I’d see a sale of the Macklowe collection,” Harry told reporters afterward. “I’m thrilled by it. Not by the economics, but by the quality being recognized by collectors.”

The Billboard as Psychological Warfare

Before the sale, Macklowe offered his own commentary on the divorce. In March 2019, he plastered 42-by-24-foot photographs of himself and new wife Patricia on the facade of 432 Park Avenue—the building visible from his ex-wife’s apartment. The New York Times called it a “taunt.” Macklowe called it “a proclamation of love.” The photos remained displayed on one of Manhattan’s tallest buildings, impossible to ignore from virtually anywhere in Midtown.

The gesture encapsulated everything about Macklowe: the grandiosity, the vindictiveness, the absolute refusal to do anything quietly. He had built the city’s most controversial tower and now used it as a personal billboard to mock his former wife. Rules of decorum, like rules of demolition, existed for other people.

The Hamptons Connection: Georgica Pond Wars

Macklowe’s approach to East Hampton mirrors his Manhattan tactics. He owns property on Georgica Pond, the body of water surrounded by estates belonging to Steven Spielberg, Calvin Klein, and other billionaires. In 2017, during his divorce proceedings, he purchased a 2.7-acre estate at 64 West End Avenue for $10.35 million and moved in with Patricia.

The property sat directly across from the 9,000-square-foot home he had shared with Linda—designed in 1989 and still owned by his ex-wife. Some might call the purchase strategic positioning. Others might call it psychological warfare. Macklowe declined to comment.

In 2024, he listed the property for $38 million, but complications arose. East Hampton Village officials accused him of illegal land clearing and unpermitted construction that endangered surrounding wetlands. Aerial photos showed huge swaths of lawn where trees once stood, with sod extending to the water’s edge. The building inspector noted 21 violations and revoked the certificate of occupancy. As of early 2025, the asking price had dropped to $32.5 million, though potential buyers still cannot legally occupy the home until violations are resolved.

“He basically made his own beach,” one village official told the East Hampton Star. The pattern repeats: act first, seek permission later, pay fines if necessary. In the 1990s, Macklowe had battled neighbor Martha Stewart over trees and shrubs he planted on her property. The legal niceties were still being debated when Stewart sold her home.

What Harry Macklowe’s Fortune Reveals About Power

Macklowe’s $2 billion net worth represents more than real estate success. It represents a particular American archetype: the self-made destroyer and creator who treats obstacles as temporary inconveniences and rules as suggestions. The snow-shoveling kid from New Rochelle proved that vision combined with absolute ruthlessness could reshape a city’s skyline.

At 88, he continues acquiring properties. The September 2025 purchase of 809 Madison Avenue signals ongoing ambition. His son William runs a competing firm after their public falling out. His daughter Elizabeth divorced Kent Swig, the son-in-law who once managed Harry’s projects. The family that built together has scattered, leaving Harry with his new wife, his towers, and his controversies.

The One Wall Street conversion—a $2 billion transformation of a landmark Art Deco building into 566 luxury apartments—represents his current focus. It’s the largest office-to-residential conversion in New York City history. When asked about the challenges, Macklowe maintains his signature languid confidence. “We have a very elegant building,” he told Spear’s magazine. “I think we’ve done a very, very good job.”

For stories of real estate titans who reshaped the Hamptons and Manhattan through sheer force of will, contact Social Life Magazine about feature opportunities. Experience the exclusive networking where deals get done at Polo Hamptons.

The midnight demolition happened 40 years ago. The buildings are long gone, replaced by a hotel Macklowe lost and regained and lost again. The contractor who swung the wrecking ball lies in a Brooklyn cemetery, murdered in a mob hit. Yet Harry Macklowe remains, still building, still demolishing, still plastering his image on the sides of skyscrapers. The snow-shoveling kid proved something that night in 1985: if you’re willing to tear down anything standing in your way, you can build whatever you want. The question is whether the world you create is worth living in.

Related Articles:

Steven Spielberg Net Worth: The $4B Fortress on Georgica Pond

Billionaire Neighbors: The $100m Estates in the Hamptons