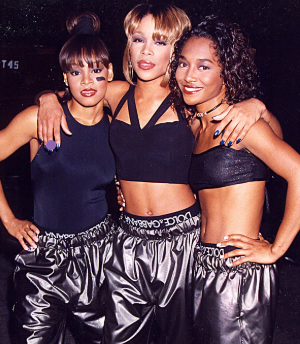

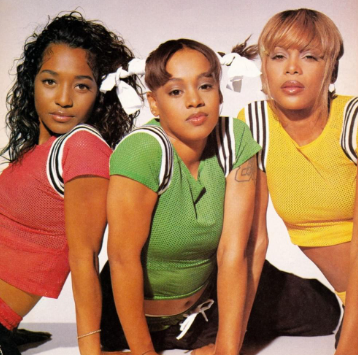

On July 3, 1995, the best-selling American girl group of all time filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. TLC had just released CrazySexyCool, an album that would go on to become the only album by a female group to ever receive diamond certification. They had two Grammys, 14 million copies sold. They had $3.5 million in debt and each member was taking home less than $50,000 a year.

If you want to understand why 90s music icons talk about the industry like it’s a crime scene, start here. TLC’s financial story isn’t just the most extreme example of record deal exploitation in the decade. It’s the one that made the exploitation impossible to ignore.

The Contract That Ate a Fortune

Tionne “T-Boz” Watkins, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes, and Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas signed with LaFace Records and Pebbitone, a management and production company run by singer Perri “Pebbles” Reid, in 1991. The women were teenagers. They didn’t have independent legal counsel. The contract gave them 7% of album sales, which sounds thin but looks generous compared to what actually happened.

After LaFace and Pebbitone deducted recording costs, video production, promotion, tour support, advances, airline travel, hotels, food, clothing, and every other conceivable expense, TLC received approximately 56 cents per album sold. Split three ways. According to The New York Times, the group ultimately received about 1% of the $175 million in revenue their albums generated.

The structure was particularly insidious because the production, management, and record label were essentially under the same corporate umbrella. TLC couldn’t earn money elsewhere. They couldn’t negotiate independently. The more successful the album became, the more expenses were charged against their earnings. Success and debt moved in the same direction.

The Grammy Speech That Changed the Conversation

At the 1996 Grammy Awards, after winning Best R&B Album for CrazySexyCool, Chilli made the statement that became the most quoted line in 90s music business history: “We’ve sold 10 million albums worldwide. We’re as broke as broke can be.” Left Eye added: “I hope we go down in history for being something more than just another famous act that got ripped off.”

The public spectacle forced a reckoning. TLC sued Pebbitone and LaFace Records. After two years of legal proceedings, a settlement allowed the group to exit their Pebbitone contract and renegotiate with LaFace directly. The new deal was better. But better than exploitative is still a low bar.

The Comeback and the Tragedy

TLC’s third album, FanMail, dropped in 1999 and debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 with 318,000 first-week sales. It went six times platinum and produced “No Scrubs” and “Unpretty,” both number-one singles. The renegotiated contract meant the group actually earned meaningful revenue this time.

Then in 2002, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes died in a car accident in Honduras at age 30. The group lost its most outspoken member and the person who had been most vocal about the financial injustice they’d endured. T-Boz and Chilli continued as a duo, honoring Lopes’ legacy while rebuilding.

In a remarkable recent revelation, T-Boz disclosed that the group paid $1 million per letter to buy back the rights to their own name. Three million dollars total to own the word “TLC.” She didn’t say who they purchased it from. “You know from whom,” she said. “We ain’t gonna say.”

Where TLC’s Money Stands in 2026

TLC’s combined estimated net worth in 2026 hovers around $20 million. Individually, T-Boz and Chilli are each estimated in the $6 to $10 million range. These numbers represent a recovery, but they’re staggeringly modest for a group that sold 65 million records and generated hundreds of millions in industry revenue.

For context: Victoria Beckham of the Spice Girls, who sold fewer total records than TLC, is worth $450 million. The difference isn’t talent or popularity. It’s contract structure, ownership, and the compounding effect of early financial disadvantage. TLC started in a hole. They’ve been climbing out ever since.

The group continues to earn from touring, merchandise, and streaming royalties. Their catalog, particularly CrazySexyCool and FanMail, generates steady passive income. A 2017 self-titled album funded through Kickstarter demonstrated their enduring fan base and their independence from the label system that nearly destroyed them.

The Structural Lesson in TLC’s Story

TLC’s financial story gets told as a cautionary tale about bad contracts, and it is that. But it’s also a story about information asymmetry at its most extreme. Three teenagers signed an agreement whose implications they couldn’t possibly understand, with a counterparty that understood compound value better than they did. The system wasn’t broken. It was working exactly as designed, just not for the artists.

For anyone advising high-net-worth individuals, family offices, or young talent entering complex contractual arrangements, TLC’s story carries a lesson that transcends music: the most expensive education is the one you get after signing the contract. Independent counsel isn’t overhead. It’s infrastructure. And the people who tell you not to worry about the details are usually the ones profiting from your ignorance.

TLC sold 65 million records. They filed for bankruptcy at their commercial peak. They paid $3 million to own their own name. And they’re still standing. That’s not just a music story. That’s a survival story. And the fact that it keeps happening means it’s also a warning.

Want to feature your brand alongside stories like this? Contact Social Life Magazine about partnership opportunities. Join us at Polo Hamptons this summer. Subscribe to the print edition or join our email list for exclusive content. Support independent luxury journalism with a $5 contribution.