By David Hornung, Co-Founder & Principal Designer, D&J Concepts

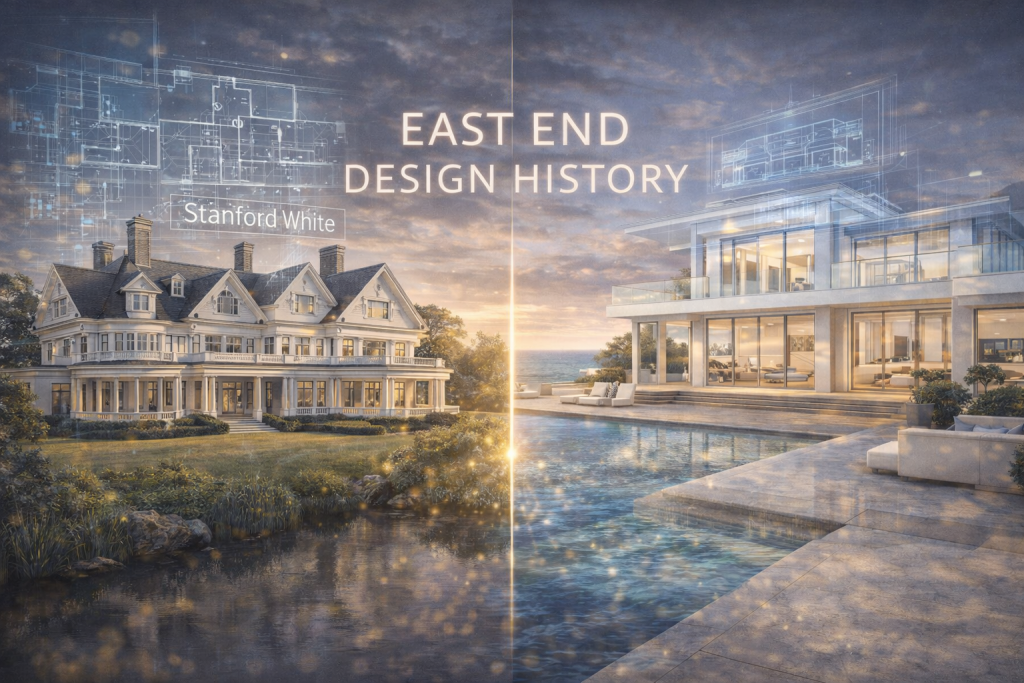

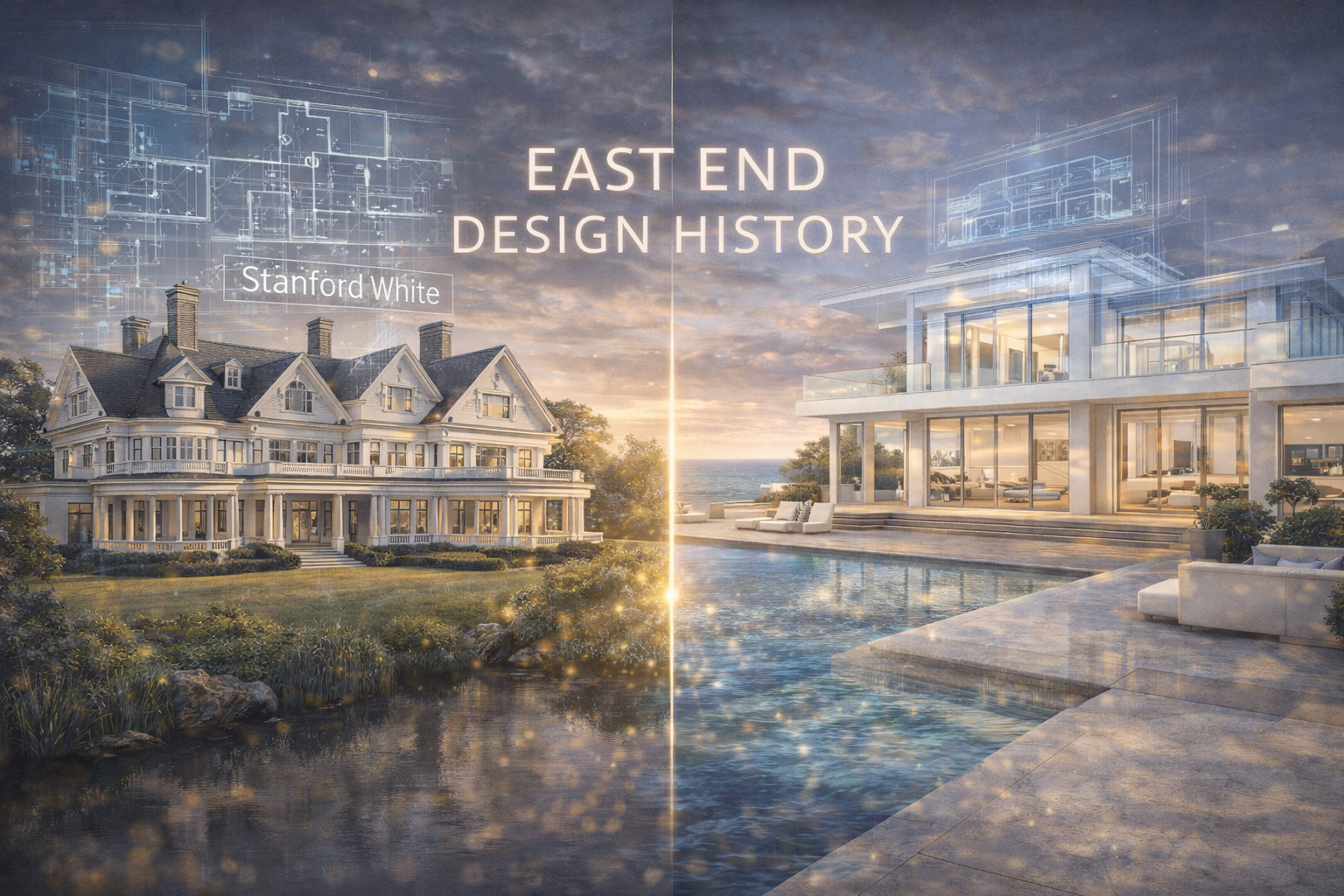

Every house on the East End carries a ghost. The ghost wears cedar shingles. It was designed by Stanford White in 1883, and it has been copied, rejected, reinterpreted, and ultimately honored by every generation of builders who came after. Hamptons design history is not a sequence of styles. It is a 140-year argument about a single question: how should Americans live at the edge of the ocean? The answers have changed. The question has not.

David Hornung has spent 25 years working inside that argument. Every renovation at D&J Concepts begins with the same investigation: what does this house owe to the East End’s design lineage, and what can it borrow from it? Understanding Hamptons design history is not an academic exercise. It is the prerequisite for designing a room that will still feel correct in 2040.

The Railroad and the Revolution: 1870 to 1900

Before the Long Island Rail Road reached Southampton in 1870, the East End was farmland. Saltbox homes and post-and-beam barns built by English settlers defined the architectural landscape. Cedar shingles covered everything because cedar was local, abundant, and resistant to the salt air that corroded other materials. The architectural vernacular was functional, not aspirational.

The railroad changed everything. Manhattan’s industrial fortunes needed summer retreats, and the South Fork offered what Newport increasingly did not: space, light, and a coastline oriented for maximum sunset drama. The architects followed the money. McKim, Mead & White, the firm that would reshape American architecture, began designing what they called “cottages” on the East End in the early 1880s. Stanford White’s contribution to Hamptons design history was foundational: he adapted the shingled vernacular of local farmhouses into a new architectural language that combined informality with grandeur.

White’s Shingle Style homes established proportions that persist today. Wide porches invited the maritime air inside. Double-height living halls created gathering spaces scaled for entertaining. Generous window groupings harvested the particular quality of East End light, which maritime humidity softens and the Atlantic’s reflective surface amplifies. Even the Seven Sisters, the Montauk Association cottages White designed in the 1880s, demonstrate his understanding that Hamptons architecture must respond to geography first and fashion second.

Parish-Hadley and the Interior Revolution: 1960 to 1994

White gave the Hamptons its exterior. Sister Parish gave it an interior vocabulary. Born Dorothy May Kinnicutt in 1910, Parish built her practice on a premise that contradicted the prevailing design establishment: rooms should look as though they had been lived in for generations, even when they were assembled last month. Chintz slipcovers over deep sofas. Hooked rugs on painted floors. Botanical prints in simple frames. Wicker baskets holding everything from firewood to magazines.

Parish’s partnership with Albert Hadley, formalized in 1962, created the most influential interior design firm of the twentieth century. Their client list read like a Social Register entry: Astors, Mellons, Paleys, Rockefellers, Whitneys. When the Kennedys needed someone to reimagine the White House, they hired Sister Parish. Her impact on Hamptons design history extended beyond aesthetics. She established the principle that comfort outranks formality on the East End, an idea that remains operative in every serious design conversation today.

Furthermore, Parish-Hadley functioned as a design academy. Bunny Williams, Mark Hampton, David Easton, and a roster of other designers apprenticed at the firm before establishing their own practices. Each carried forward Parish’s instinct for layered, livable rooms while introducing new material palettes and spatial approaches. As Architectural Digest documented throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Parish-Hadley alumni network effectively controlled the visual identity of Hamptons interiors for three decades.

The Glass Interruption: Modernism Arrives

Mid-century modernism reached the Hamptons later than it reached California or Connecticut, but when it arrived, the impact was seismic. Architects like Norman Jaffe, Andrew Geller, and later Charles Gwathmey introduced glass walls, cantilevered volumes, and spatial transparency to a landscape that had known only shingles and clapboard. The modernist houses that line Meadow Lane in Southampton and scatter through Amagansett’s oceanfront represent a fundamentally different proposition about how to inhabit the East End.

Where White’s Shingle Style homes sheltered inhabitants from the ocean landscape, modernist glass houses immersed them in it. Where Parish-Hadley layered rooms with textiles and objects, modernist interiors stripped surfaces to essentials. The tension between these two approaches has never resolved, and that productive tension defines Hamptons design history’s most creative period. Jaffe’s work at 170 Meadow Lane, later owned by Jay Sugarman and designer Kara Mann, exemplifies how modernist architecture could achieve warmth without abandoning its principles.

The hedge fund era of the early 2000s accelerated this tension. New money arrived with new tastes, commissioning tear-downs and contemporary builds that introduced architectural vocabulary the East End had never seen. Firms like McAlpine Tankersley bridged the gap, designing homes that honored the Shingle Style tradition while incorporating contemporary spatial planning. That negotiation between preservation and innovation characterizes the best Hamptons architecture today.

Quiet Luxury: The Current Chapter

The post-2020 shift in Hamptons design history was accelerated by the pandemic but had been building for years. When the East End transformed from seasonal retreat to year-round residence for many homeowners, rooms designed for July cocktail parties needed to sustain February workdays. The performative interior, designed to impress weekend guests, gave way to the functional interior, designed to support daily life. Material quality replaced visible branding. Comfort engineering replaced decorative display.

This quiet luxury movement draws on European precedents, particularly the Belgian and Scandinavian traditions of material minimalism paired with tonal warmth. However, the best Hamptons interpretations maintain a distinctly American ease that neither Brussels nor Copenhagen quite achieves. That ease traces directly to Sister Parish’s insistence on unstudied comfort, which survives as Hamptons design history’s most enduring contribution to global residential practice.

Steve Chase anticipated this shift from his studio in Rancho Mirage decades before the market caught up. His preference for natural materials that develop patina, his refusal to impose a signature style, his insistence that design should serve the inhabitant rather than advertise the designer all align precisely with the quiet luxury principles now dominating the East End. D&J Concepts’ Method of Visual Clarity carries that philosophy into contemporary practice. For the detailed examination of how quiet luxury won the Hamptons, read Sister Parish to Now: Quiet Luxury Won the Hamptons.

What 140 Years Teach: Design Principles That Survive

After studying Hamptons design history across 25 years of active practice, David Hornung identifies five principles that survive every trend cycle. Natural light must be the primary architectural material. Cedar and other coastal materials must reference the local environment without descending into nautical cliché. Rooms must invite extended occupation, not just visual approval. Interior spaces must connect to the landscape through sight lines, materials, or both. In addition, every design decision must acknowledge the specific architectural history of the structure it inhabits.

These principles connect Stanford White’s original Shingle Style insights directly to contemporary practice. White understood that East End light required generous windows. Parish understood that East End living required genuine comfort. Chase understood that materials should tell the truth. The best contemporary Hamptons designers, whether working on a White-era restoration or a ground-up modern build, synthesize all three understandings into rooms that honor the past without being imprisoned by it.

According to Christie’s International Real Estate, properties that demonstrate this synthesis consistently command premiums over homes that merely reference a single period. Buyers at the $15 million level can identify the difference between design intelligence and historical cosplay. Hamptons design history is not a menu of styles to choose from. It is a conversation to join, and the entry requirement is understanding what has already been said.

Design Within the Tradition

D&J Concepts brings 25 years of East End expertise and deep understanding of Hamptons design history to every project. Through the Method of Visual Clarity, David Hornung shows clients how their renovation connects to the architectural tradition while creating something genuinely new. Contact us to discuss features, advertising, or partnerships. For Polo Hamptons tickets and sponsorship, visit polohamptons.com.

Subscribe to Social Life Magazine for insider Hamptons design and history coverage. Join our email list. Print subscriptions available. Support independent luxury journalism with a $5 contribution. Continue with Sister Parish to Now: Quiet Luxury Won the Hamptons and Beyond Parish-Hadley: Modern Hamptons Living.