The Artwork Frida Kahlo Produced: Scale and Scarcity

Kahlo created approximately 200 paintings during her lifetime, though estimates vary. Of these, 55 were self-portraits. The total output seems modest compared to prolific contemporaries, but context matters: chronic pain from her bus accident and subsequent surgeries limited her working capacity. Moreover, she painted primarily on small surfaces, often metal sheets or masonite boards rather than large canvases. The intimate scale reflected both her domestic working conditions and her focus on personal subject matter.

The scarcity issue compounds significance. In 1984, Mexico declared her works national cultural patrimony, prohibiting export of pieces held within the country. Consequently, paintings in private collections outside Mexico command extraordinary premiums. Furthermore, major works rarely appear at auction because most important pieces reside permanently in institutions or in collections whose owners have no intention of selling.

This market reality shapes collector strategy. You’re unlikely to acquire a significant Kahlo painting. However, understanding her oeuvre enriches engagement with contemporary artists who reference her, informs conversations at cultural gatherings, and demonstrates the sophistication that distinguishes substantial collectors from mere purchasers.

The Essential Self-Portraits: Artwork Frida Kahlo Created That Defines Her Legacy

“I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.” This statement explains both the quantity and the quality of Kahlo’s self-portraits. Each one functions as autobiography, psychological study, and formal experiment simultaneously. Nevertheless, not all carry equal cultural weight.

The Two Fridas (1939)

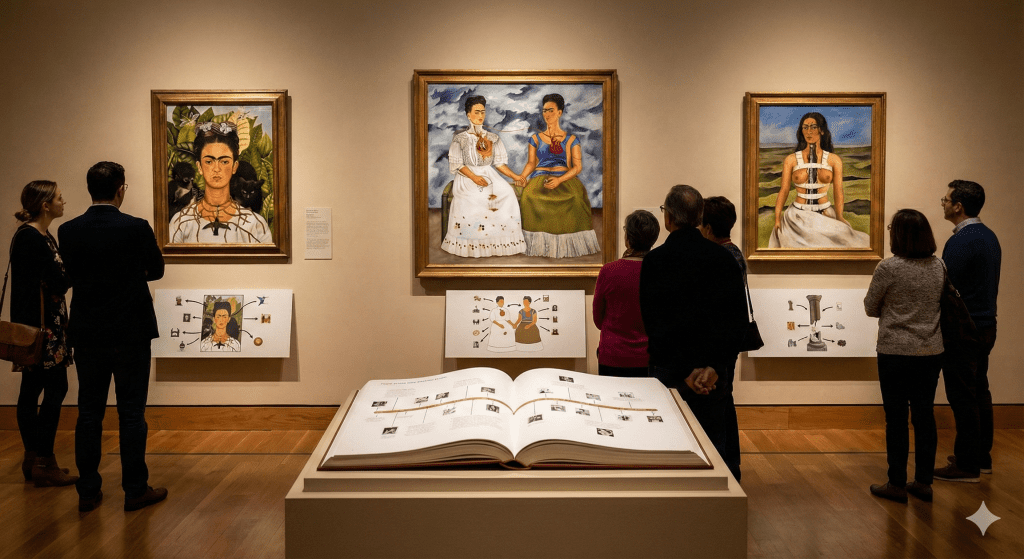

Measuring 173 by 173 centimeters, this double self-portrait represents Kahlo’s largest and arguably most ambitious work. She painted it during her divorce from Diego Rivera, depicting two versions of herself seated side by side on a green bench against a stormy sky. The European Frida wears a white Victorian dress; the Mexican Frida wears traditional Tehuana clothing. A single artery connects their exposed hearts. The European Frida’s heart bleeds onto her white skirt while the Mexican Frida holds a miniature portrait of Rivera.

The painting resides permanently at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. It cannot be sold, cannot leave Mexico, and appears in virtually every survey of twentieth-century art. This is the Kahlo painting that art historians consider essential. Additionally, it demonstrates her capacity for large-scale composition, refuting critics who dismissed her as a miniaturist.

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940)

Created the same year as The Two Fridas, this smaller work (24 by 18 inches) presents Kahlo in three-quarter profile against dense tropical foliage. A thorn necklace draws blood from her neck. A dead hummingbird hangs from the thorns like a pendant. A black cat crouches on one shoulder; a spider monkey on the other. Butterflies crown her elaborately braided hair.

Every element carries symbolic weight. The hummingbird represents Mexican folk tradition as a luck charm in love. The thorns reference both Christian iconography and her own suffering. The monkey was one of her beloved pets. Subsequently, the painting layers autobiography with religious symbolism and cultural reference in a format that became her signature approach.

Photographer Nickolas Muray, with whom Kahlo had a passionate affair, owned this painting. He gifted it to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, where it remains the collection’s most visited work. For collectors traveling domestically, this represents the most accessible major Kahlo painting in a US institution.

Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940)

Following her divorce from Rivera, Kahlo cut off the long hair he loved and painted herself in a man’s suit, scissors in hand, shorn locks scattered across the floor. Musical notation at the top reads: “Look, if I loved you it was because of your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you anymore.”

This painting hangs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It functions as feminist statement, rejection of feminine beauty standards, and direct rebuke to Rivera. Furthermore, it demonstrates Kahlo’s willingness to portray herself unflinchingly, without the flattering self-presentation that characterized most portraiture of the era.

The Wounded Body: Artwork That Confronts Suffering

No artist before or since has depicted physical suffering with Kahlo’s combination of clinical precision and emotional intensity. These paintings document her medical reality while transforming pain into visual poetry.

The Broken Column (1944)

Kahlo portrays herself nude from the waist up, her torso split open to reveal a crumbling Ionic column replacing her spine. Metal nails pierce her skin and face. She wears a surgical corset that she actually used. Tears stream down her face against a barren landscape.

The painting resides at the Museo Dolores Olmedo in Mexico City, which holds the largest collection of Kahlo works outside Casa Azul. This collection includes 25 paintings and numerous drawings, making the Olmedo essential for anyone serious about understanding Kahlo’s complete artistic development. Moreover, the museum’s location in Xochimilco offers a different Mexico City experience than the crowded Coyoacán tourist circuit.

Henry Ford Hospital (1932)

Following a miscarriage in Detroit, where Rivera was painting murals, Kahlo created one of her most harrowing images. She lies naked on a hospital bed, bleeding, connected by red ribbons to floating objects: a fetus, a snail, a pelvis model, an orchid, and medical equipment. The industrial Detroit skyline appears in the background.

This painting established the format Kahlo would use repeatedly: the prone figure surrounded by symbolic objects floating in dreamlike space. Subsequently, it influenced generations of artists exploring trauma, the body, and female experience. The work remains in the Museo Dolores Olmedo collection.

El sueño (La cama) / The Dream (The Bed) (1940)

In November 2025, this painting sold at Sotheby’s for $54.7 million, setting the record for any female artist at auction. The work depicts Kahlo asleep on a canopy bed floating in clouds, vines wrapping her body, a skeleton wired with dynamite reclining above her. She actually slept with a papier-mâché skeleton in her canopy bed. The painting had been in private hands since 1980, when it sold for $51,000. The 107,155 percent appreciation over 45 years demonstrates Kahlo’s extraordinary market trajectory.

The buyer’s identity remains undisclosed. The painting may enter a museum collection or disappear into private storage, as sometimes happens with record-breaking acquisitions. This uncertainty underscores why experiencing Kahlo’s work requires visiting the permanent collections while access remains guaranteed.

Where to See the Most Important Artwork by Frida Kahlo

Serious engagement with Kahlo’s oeuvre requires strategic museum visits. The works are distributed across institutions with varying accessibility.

Mexico City: The Essential Circuit

Three institutions hold the most significant concentrations of Kahlo paintings:

Museo Frida Kahlo (Casa Azul) in Coyoacán displays paintings created in the house where she lived, including her final work Viva la Vida (1954), Portrait of My Father Wilhelm Kahlo (1952), and Frida and the Cesarean Operation (1931). The context matters as much as the art. Additionally, her diaries, sketches, and personal effects illuminate the paintings’ creation. Advance booking is mandatory; the museum limits daily visitors.

Museo Dolores Olmedo in Xochimilco holds 25 paintings and numerous drawings, the world’s largest single collection. The Broken Column, Henry Ford Hospital, and Self-Portrait with Monkey (1945) reside here permanently. Furthermore, the hacienda setting and gardens create a more contemplative viewing environment than crowded tourist venues.

Museo de Arte Moderno in Chapultepec Park displays The Two Fridas and Las dos Fridas (Root), essential for understanding her largest and most politically significant work. The museum contextualizes Kahlo within the broader Mexican modernist movement, positioning her alongside Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros.

United States Venues

Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin holds Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, arguably the most recognizable Kahlo painting in an American collection. The center also houses Muray’s extensive archive of Kahlo photographs, providing visual documentation of the woman behind the self-portraits.

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York displays Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair and Fulang-Chang and I (1937). The latter includes a mirror frame attached to the painting, allowing viewers to see themselves alongside Kahlo and her monkey. This interactive element anticipated contemporary art’s engagement with viewer participation.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art holds Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931), a wedding portrait that captures the couple’s early relationship before its turbulent middle years. The painting demonstrates Kahlo’s technical development and her awareness of her secondary role as Rivera’s wife during that period.

National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC displays Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937), painted during or shortly after her affair with the exiled revolutionary. The museum also holds letters Kahlo sent to her doctor, Leo Eloesser, providing biographical context for the artwork.

What Sophisticated People Say About Artwork by Frida Kahlo

Collector conversations require more than recognition. Demonstrating genuine knowledge means understanding the critical debates surrounding her work.

The Surrealism Question

André Breton, the founder of Surrealism, called Kahlo’s work “a ribbon around a bomb” and invited her to exhibit in Paris. She rejected the Surrealist label: “I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.” This distinction matters. Surrealists accessed the unconscious through automatic techniques. Kahlo’s imagery, however dreamlike in appearance, derived from specific biographical experience. Consequently, categorizing her as Surrealist misunderstands her method and intention.

The Diego Question

During her lifetime, Kahlo was often introduced as Diego Rivera’s wife. Today, her auction records dwarf his, her museum draws more visitors than any Rivera site, and her image recognition exceeds almost any artist except Van Gogh and Picasso. However, reducing her to a reversal narrative, the overlooked wife who surpassed her famous husband, simplifies both their relationship and her achievement. Rivera genuinely championed her work. She genuinely loved him despite his infidelities. Their artistic dialogue enriched both practices.

The Fridamania Question

Her face appears on tote bags, refrigerator magnets, and Halloween costumes. Does commercial appropriation diminish her artistic standing? Serious collectors argue no. The commodification of her image operates separately from the valuation of her paintings. Indeed, popular recognition may enhance market value by creating demand among new collectors entering the Latin American art market.

The Investment Perspective on Artwork Frida Kahlo Created

The $54.7 million record sale followed a consistent appreciation trajectory. Diego y yo sold for $34.9 million in 2021. Roots sold for $5.6 million in 2006, then the Latin American record. Each sale exceeded expectations, suggesting sustained rather than speculative demand.

Several factors support continued appreciation. Institutional attention keeps growing. The forthcoming Museum of Fine Arts Houston exhibition traveling to Tate Modern will introduce Kahlo to new audiences. Furthermore, the supply constraint is absolute. Mexico’s export prohibition means no new Kahlo works can enter international circulation. Additionally, women artists and Latin American artists continue gaining recognition historically denied them, benefiting Kahlo’s market position.

For collectors unable to acquire actual Kahlo paintings, related opportunities exist. Works by artists she influenced, photography by Muray and others who documented her, pre-Columbian objects similar to what she and Rivera collected, and Mexican folk art of the type she incorporated into her practice all represent adjacent collecting strategies. The serious collector builds context around a desired artist when direct acquisition proves impossible.

Artwork by Frida Kahlo You Should Know by Heart

Cultural fluency requires immediate recognition of these five works:

The Two Fridas: Her largest painting, the double self-portrait with connected hearts. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird: The iconic image with dead bird pendant, monkey, and black cat. Harry Ransom Center, Austin.

The Broken Column: Split torso revealing crumbling spine, nails piercing skin. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair: Man’s suit, scissors, shorn hair scattered on floor. MoMA, New York.

Henry Ford Hospital: Bleeding figure on hospital bed, floating symbolic objects. Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City.

Memorize these locations. Know the dates. Understand the biographical contexts. This knowledge separates the person who appreciates Kahlo from the person who merely recognizes her unibrow.

At art fairs and collector gatherings, conversations about Kahlo will continue arising. The question is whether you contribute substantively or fade into the background mumbling about monkeys. Now you know which artwork by Frida Kahlo actually matters and why. Use the knowledge wisely.

Stay Connected with Social Life Magazine

- Contact Social Life Magazine for editorial inquiries

- Experience Polo Hamptons — where culture meets sport

- Subscribe to Our Newsletter for insider access

- Print Subscription — join the conversation

- Support Independent Journalism