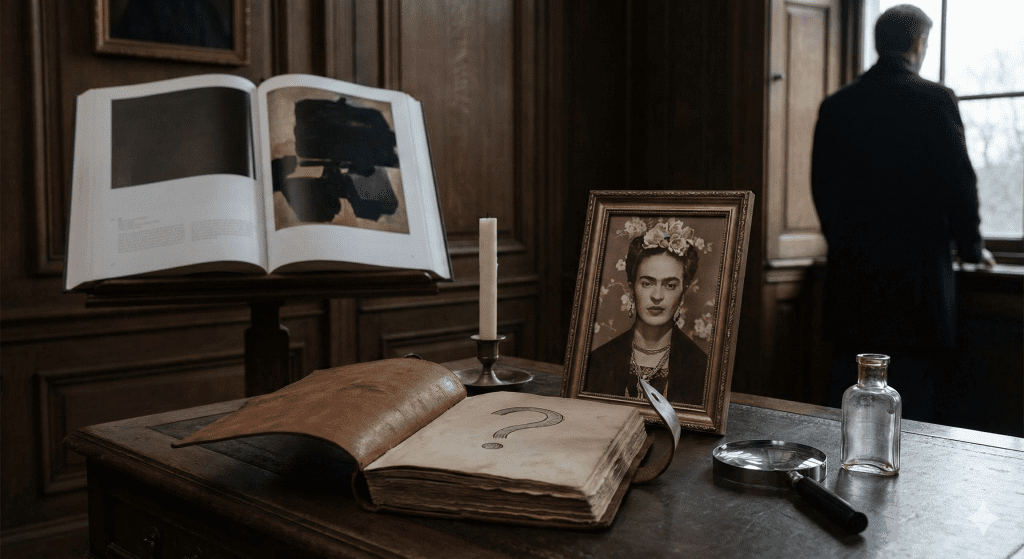

Seven decades later, Kahlo’s paintings command auction records. Her face appears on more merchandise than any artist except perhaps Van Gogh. Consequently, the question of how Frida Kahlo died matters beyond biography. The circumstances of her death, the posthumous mythology, and her transformation from Diego Rivera’s wife to the most expensive female artist in auction history form a single continuous story. Understanding the ending illuminates everything that came before.

The Final Months

Kahlo spent most of 1954 bedridden. Bronchopneumonia weakened her already fragile constitution. The previous year, in August 1953, surgeons had amputated her right leg below the knee due to gangrene. She wrote in her diary: “They amputated my leg six months ago, they have given me centuries of torture and at moments I almost lost my reason.”

Despite her condition, she remained politically active. On July 2, 1954, eleven days before her death, Kahlo left Casa Azul in a wheelchair to join Diego Rivera at a demonstration protesting the CIA-backed coup against Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz. Photographs from that day show her gaunt but defiant, holding a banner alongside Rivera. The exertion worsened her illness.

Her nurse monitored her medication carefully. Kahlo had been prescribed a maximum of seven painkillers daily. On the night of July 12, she reportedly took eleven. Her nurse found her dead the following morning at approximately 6:00 AM.

The Official Cause and Its Critics

Psychiatrist Dr. Ramón Parres, who had treated Kahlo for depression and paranoia in her final years, signed the death certificate. The listed cause was pulmonary embolism, a blood clot blocking an artery in the lungs. Given her decades of immobility, multiple surgeries, and compromised circulation, this diagnosis was medically plausible.

No autopsy was performed. The body was cremated rapidly, preventing future investigation. These facts fuel alternative theories.

Biographer Martha Zamora, author of Frida Kahlo: The Brush of Anguish, has suggested suicide or accidental overdose as possible causes. The nurse’s count of excessive painkillers supports this interpretation. Kahlo’s diary entries from her final days contained drawings of skeletons and angels. Her last written words read: “I joyfully await the exit, and I hope never to return.” Biographer Hayden Herrera interprets the final drawing, a black angel, as the Angel of Death.

Rivera, present at the cremation, later wrote that the moment her body entered the flames, she appeared to sit up suddenly, her hair forming a halo of fire around her face. Whether literal or metaphorical, the image captures the theatrical quality that defined both her life and her death.

Diego Rivera’s Response

Rivera described July 13, 1954, as “the most tragic day of my life.” Despite their turbulent marriage, their divorces, their mutual infidelities, and their frequent separations, he never fully recovered from her death. He wrote in his autobiography: “The most wonderful part of my life was my love for Frida. When she died, a part of me died too.”

He ensured her legacy would survive. Kahlo had requested that Casa Azul become a museum. Rivera established the trust that still manages the property and her artistic estate. He sealed a bathroom containing her personal effects with instructions not to open it until fifteen years after his own death. The room was finally opened in 2004, fifty years after Kahlo died, revealing over 300 garments, orthopedic devices, and personal artifacts that reshaped understanding of her life.

Rivera remarried the following year, to his art dealer Emma Hurtado, but devoted his remaining years partly to protecting Kahlo’s reputation and ensuring her work remained accessible. He died in 1957, three years after her.

The Posthumous Transformation

When Kahlo died in 1954, she was known primarily as Diego Rivera’s wife. Her obituaries mentioned her paintings but emphasized her role as companion to Mexico’s most famous muralist. Few outside Mexico had seen her work. Even fewer considered her a major artist in her own right.

The reversal began slowly. Feminist art historians in the 1970s, searching for overlooked female artists, discovered Kahlo’s unflinching self-portraits and recognized their power. Historian Hayden Herrera published Frida: A Biography in 1983, providing the first comprehensive English-language account of her life. The book became a bestseller and introduced Kahlo to international audiences.

Herrera’s research revealed that Kahlo’s feminist significance first emerged within the Chicano community along the U.S.-Mexico border, where migrant women identified with her exploration of hybrid identity, physical suffering, and cultural pride. The 1970s feminist movement amplified this recognition, claiming Kahlo as an icon of female creativity and resistance to patriarchal art institutions.

The 2002 biopic Frida, starring Salma Hayek, cemented her popular culture status. Suddenly her face was everywhere: on t-shirts, tote bags, coffee mugs, and Halloween costumes. “Fridamania” had arrived.

The Market Reversal

The financial transformation parallels the cultural one. In 1939, Kahlo wrote with astonishment that actor Edward G. Robinson had purchased four of her paintings for $200 each at her Julien Levy Gallery exhibition in New York. That represented significant money for her at the time. Today, a single painting sells for more than she earned in her entire lifetime.

In November 2025, El sueño (La cama) sold at Sotheby’s for $54.7 million, setting the record for any female artist at auction and for any Latin American artist in history. The painting had last sold in 1980 for $51,000. The appreciation over 45 years exceeded 107,000 percent.

Diego Rivera’s auction record stands at $14.13 million. The gap between husband and wife now exceeds $40 million and continues widening. The muralist who overshadowed her during their lifetimes is now, in market terms, her footnote.

This reversal reflects broader trends in art world valuation. Female artists historically underrepresented in museum collections and auction records are being reevaluated. Latin American art, long marginalized by European and North American markets, commands increasing attention. Kahlo benefits from both corrections simultaneously.

Why Her Legacy Endures

Multiple constituencies claim Kahlo as their icon. The feminist movement embraces her unflinching depiction of female experience: miscarriage, infertility, desire, and rage. The disability community recognizes her as rare representation of chronic pain and physical limitation depicted with dignity rather than pity. The LGBTQ+ community claims her bisexuality and gender fluidity, documented in her relationships with both men and women. Mexican cultural nationalists celebrate her indigenous aesthetic and revolutionary politics.

Her great-niece Cristina Kahlo, interviewed by Google Arts & Culture, observed that “Fridamania” often emphasizes anecdote over art. “Unfortunately, in many cases, Frida Kahlo is known only for the anecdotal part of her life and is recognized as a personality, while her more important side, her artistic legacy, is often overlooked.”

This criticism has merit. The commodification of her image sometimes obscures the paintings themselves. But even commercial exploitation testifies to her enduring power. Her face functions as shorthand for artistic authenticity, feminine strength, and cultural resistance. Whether that constitutes appreciation or appropriation depends on context.

The Paintings That Outlasted the Questions

How did Frida Kahlo die? We will never know with certainty. The absence of autopsy, the rapid cremation, the contradictory evidence of medication counts and diary entries, all preclude definitive answers. Was it pulmonary embolism, accidental overdose, or intentional suicide? The medical records cannot tell us. The cremated body cannot tell us. Only speculation remains.

What we do know is what survives: approximately 200 paintings, most measuring less than two feet in any dimension, created between her bus accident in 1925 and her death in 1954. The Broken Column documents chronic pain with clinical precision. The Two Fridas explores dual identity with surgical detachment. Henry Ford Hospital transforms miscarriage into visual poetry. Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird layers religious iconography over personal suffering.

These works require no biographical context to affect viewers. They communicate directly, viscerally, across language and culture. The mystery of her death adds romantic intrigue, but the paintings justify themselves independent of mythology.

What Sophisticated People Say

At cultural gatherings, the question of how Frida Kahlo died inevitably arises. Position yourself with these observations:

On the mystery: “The official cause was pulmonary embolism, but no autopsy was performed and the body was cremated within hours. Her nurse counted the painkillers. Her diary drawings suggest she anticipated death. We’re left with ambiguity that serves the mythology rather than history.”

On the market reversal: “She sold paintings for $200 in 1939. El sueño brought $54.7 million in 2025. Diego Rivera’s record is $14 million. The wife who was introduced as his companion now commands four times his auction prices.”

On Fridamania: “Her face on tote bags troubles some scholars who feel the commercialization obscures the art. But the popularity also drives museum attendance and introduces new audiences to the actual paintings. Consequently, the commodification and the preservation work in parallel.”

On her contemporary relevance: “Kahlo painted her reality during an era that demanded women remain decorative. She depicted miscarriage, chronic pain, and marital betrayal with unflinching honesty. That directness explains why feminist, disability, and LGBTQ+ communities continue claiming her as representative.”

The Legacy in Concrete Terms

Visit the museums. Casa Azul draws more visitors than any other museum in Mexico. The new Museo Casa Kahlo opened in September 2025, offering access to her childhood environment and family archives. Museo Dolores Olmedo holds the world’s largest private collection of her paintings. Museo de Arte Moderno displays The Two Fridas in its permanent galleries.

Attend the exhibitions. The Museum of Fine Arts Houston opens “Frida: The Making of an Icon” in January 2026. Tate Modern follows in June 2026 with a comprehensive retrospective. These institutional commitments ensure her work remains visible to new generations.

Understand the facts. She created approximately 200 paintings, 55 of which were self-portraits. Mexico declared her works national cultural patrimony in 1984, prohibiting export from the country. The scarcity of available works drives auction prices. The mythology drives popular interest. Together, they create a self-reinforcing cycle of cultural and financial appreciation.

The Question That Remains

How did Frida Kahlo die? The honest answer is: we don’t know, and we never will. Pulmonary embolism remains the official cause. Suicide remains a plausible alternative. Accidental overdose cannot be ruled out. The cremation foreclosed forensic investigation. The participants are all dead.

Perhaps the ambiguity is appropriate. Kahlo constructed her identity throughout her life, changing her birth year to align with the Mexican Revolution, adopting indigenous costume to signal cultural allegiance, transforming medical suffering into artistic mythology. Even her death resists definitive interpretation.

What matters is what she left behind. The paintings survive. The house survives. The influence on contemporary artists, from Tracey Emin to Cindy Sherman, survives. The market records keep breaking. The museum attendance keeps climbing. The tote bags keep selling.

Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, at Casa Azul in Coyoacán. The cause remains uncertain. The legacy is beyond question.

Stay Connected with Social Life Magazine

- Contact Social Life Magazine for editorial inquiries

- Experience Polo Hamptons — where culture meets sport

- Subscribe to Our Newsletter for insider access

- Print Subscription — join the conversation

- Support Independent Journalism

The Complete Frida Kahlo Series

- Frida Kahlo Facts: What Serious Collectors Actually Need to Know

- Frida Kahlo Blue House Mexico: The Insider’s Guide to Casa Azul

- Artwork Frida Kahlo: Which Paintings Actually Matter and Why

- Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: The Partnership That Explains Everything

- The Broken Column Frida Kahlo: The Painting That Makes Everyone Look Away

- Frida Kahlo Museum Guide: The Complete Mexico City Circuit