The art world lost its most incandescent star that Friday. But in the calculus of legacy, Jean-Michel Basquiat death marked not an ending but a strange, posthumous beginning. The works that sold for $19,000 in his lifetime would eventually command $110.5 million at auction. The graffiti kid who slept on park benches would become the most expensive American artist ever sold.

The Weight of Being First

Fame arrived for Basquiat like a tidal wave. By twenty-one, he had become the youngest artist ever exhibited at Documenta in Kassel, Germany. By twenty-two, he was showing at the Whitney Biennial. His paintings sold for $25,000, then $50,000, then more. Collectors couldn’t write checks fast enough.

But the art world’s embrace came with conditions that slowly poisoned him. Critics deployed words like “primitive,” “fetish,” and “tough street-voodoo artist” to describe his work. One collector couple arrived at his studio carrying a bucket of fried chicken. New York taxis refused to stop for him regardless of his fame or fortune, so he traveled exclusively by limousine.

“They still call me a graffiti artist,” Basquiat told Vanity Fair with unmistakable bitterness. “They don’t call Keith or Kenny graffiti artists anymore.” He understood what he was to the galleries: a mascot, a curiosity, a way for wealthy whites to purchase proximity to authentic urban danger. The tokenism gnawed at him constantly.

Warhol’s Shadow and the Unraveling

Andy Warhol had been his anchor. The Pop Art legend saw genuine brilliance in the young painter and reportedly helped keep him away from heroin during their collaboration years. Together they produced over one hundred joint works between 1984 and 1985, a creative dialogue between generations that electrified the downtown scene.

Then came the 1985 Tony Shafrazi Gallery exhibition. Critics savaged the collaboration. One reviewer asked the question Basquiat dreaded most: “Who is using whom here?” The New York Times suggested he was merely Warhol’s “mascot.” The public humiliation fractured something essential in both men.

When Warhol died unexpectedly on February 22, 1987, following routine gallbladder surgery, Basquiat lost more than a collaborator. He lost the one person who seemed to genuinely understand the isolation of his position. “It put him into a total crisis,” recalled Fred Brathwaite. “He couldn’t even talk.”

Donald Rubell, the collector, offered perhaps the most haunting assessment: “The death of Warhol made the death of Basquiat inevitable. Andy was the one person who always seemed able to bring Jean-Michel back from the edge. After Andy was gone, there was no one.”

The Final Eighteen Months

The last year and a half of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s life became a study in contradiction. His artistic output remained prolific despite personal turmoil. He traveled to Paris for exhibitions at the Yvon Lambert Gallery, to Tokyo for shows at Akira Ikeda Gallery, to Düsseldorf for Hans Mayer. He designed a Ferris wheel for an ephemeral amusement park in Hamburg.

Yet his heroin consumption spiraled to reported levels of a hundred bags per day, exchanging paintings now worth millions for another fix. “They tell me the drugs are killing me,” Basquiat confided to a friend, “but when I stop using, they say my art is dead.” The trap was complete.

In June 1988, Basquiat traveled to Maui in a final attempt at sobriety. He claimed there was no heroin in Hawaii. He told Glenn O’Brien he was “feeling really good.” When he returned to New York in July, he encountered Keith Haring on Broadway. It marked the only time Basquiat ever directly discussed his drug problem with his old friend.

Ten days before a planned trip aimed at curing his addiction, he overdosed in the loft on Great Jones Street.

Riding with Death: The Last Canvas

Among Basquiat’s final paintings, one work stands as an eerie premonition. “Riding with Death” depicts a dark-skinned figure mounted atop a skeletal horse against a muted brown background. The composition is sparse and haunting, stripped of the frenetic color explosions that characterized his earlier work.

Art historians have traced its inspiration to a Leonardo da Vinci drawing. But the emotional weight feels autobiographical. The rider’s eyes are crossed out. The skeleton turns its head toward the viewer with an unblinking gaze. Death carries its passenger toward an inevitable destination.

Fred Brathwaite wrote what might serve as Basquiat’s epitaph: “He lived like a flame. He burned so bright that he shone. Then the fire went out. But the embers are still hot.”

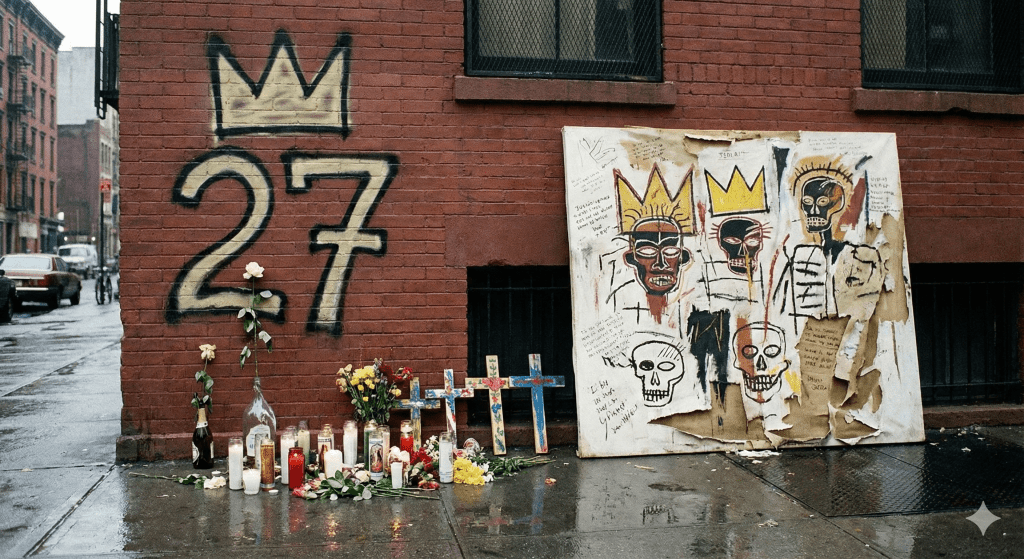

The 27 Club and Cultural Mythology

Jean-Michel Basquiat death enrolled him in rock and roll’s most tragic fraternity. The 27 Club had already claimed Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison in the span of two years between 1969 and 1971. Kurt Cobain would join them in 1994, Amy Winehouse in 2011.

Basquiat remains the only visual artist among the club’s most famous members. But the pattern holds: meteoric talent, crushing fame, substance abuse as both escape and accelerant. Scientific research has debunked the statistical significance of deaths at twenty-seven. Yet the mythology persists because it contains an emotional truth about the price of genius.

A 2024 study in Scientific American found that famous people who die at twenty-seven experience a measurable boost in posthumous fame beyond what other factors would predict. The 27 Club myth has become self-reinforcing. We remember the brilliant dead at that age more vividly precisely because of the legend.

The Memorial and the Market

A private funeral was held on August 17, 1988, at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel on Madison Avenue. Keith Haring attended alongside Francesco Clemente and Paige Powell. Jeffrey Deitch delivered the eulogy. Basquiat was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

On November 5, three hundred friends and admirers gathered at Saint Peter’s Church for a public memorial. Gray, his former band, performed. Fab 5 Freddy read Langston Hughes. Suzanne Mallouk, his former girlfriend, recited A.R. Penck’s “Poem for Basquiat.” Keith Haring would later create “A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat” in tribute.

In the Vogue obituary Haring wrote: “He truly created a lifetime of works in ten years. Greedily, we wonder what else he might have created, what masterpieces we have been cheated out of by his death. But the fact is that he has created enough work to intrigue generations to come.”

That prediction proved prophetic. Basquiat left behind approximately 600 paintings, 1,500 drawings, and countless sculptures and mixed-media pieces. The body of work has only grown more valuable with each passing decade.

57 Great Jones Street: A Legacy Preserved

In October 2025, New York City officially co-named the block between Bowery and Lafayette Street as Jean-Michel Basquiat Way. His sister Lisane joined city council members for the unveiling of commemorative street signs. A plaque now adorns the building where he lived and died.

The loft at 57 Great Jones Street has since been rented by actress Angelina Jolie as a showroom and curatorial space for her fashion brand. The walls that once held Basquiat’s paint-splattered Armani suits and hundred-dollar bills thrown from limousine windows now house haute couture. The neighborhood he helped define through his presence continues to trade on his legend.

What Collectors Should Understand

Jean-Michel Basquiat death created the conditions for his market dominance. The truncated career means finite supply. The tragic narrative adds emotional weight to every canvas. The racism he endured during his lifetime has been reframed as evidence of his prescience and courage.

For collectors navigating the Hamptons art scene, Basquiat represents both inspiration and caution. His trajectory from homelessness to auction records demonstrates art’s capacity to transcend circumstance. His death reminds us that the market’s demands can consume even its greatest talents.

Early collectors like Isabella del Frate Rayburn recognized his genius before the prices became stratospheric. Today’s collectors face a different landscape, one where Basquiat has become shorthand for cultural capital among young millionaires.

Understanding the man behind the myth matters. Basquiat was not merely a brand to be licensed onto sneakers and skateboards. He was an intellectual who read voraciously, a poet who embedded text into every composition, a Black artist who insisted on placing Black protagonists at the center of his canvases when the gallery world had almost none.

His meteoric rise from Brooklyn street artist to $110 million auction king only gains meaning when set against the cost of that ascent. The 27 Club claims geniuses who burn too bright. Jean-Michel Basquiat death at twenty-seven years old sealed his legend precisely because he had already created enough to haunt us forever.

The Hamptons galleries that now feature his estate prints and exhibition materials carry forward a complicated inheritance. Every crown, every skull, every crossed-out word contains multitudes. The Hamptons art scene offers collectors the opportunity to engage with that legacy directly.

But engagement requires honesty. Jean-Michel Basquiat was not a mascot or a curiosity. He was an artist who told uncomfortable truths about race, power, and the American dream’s broken promises. His death at twenty-seven was not romantic. It was the predictable result of a system that consumed what it claimed to celebrate.

The embers are still hot.