That’s a mistake. The Broken Column by Frida Kahlo is arguably the most unflinching depiction of chronic pain ever painted. Consequently, understanding what Kahlo created in 1944 transforms how you see not just her work but the entire tradition of self-portraiture. This isn’t suffering as metaphor. This is suffering as documentary evidence.

What You’re Actually Looking At

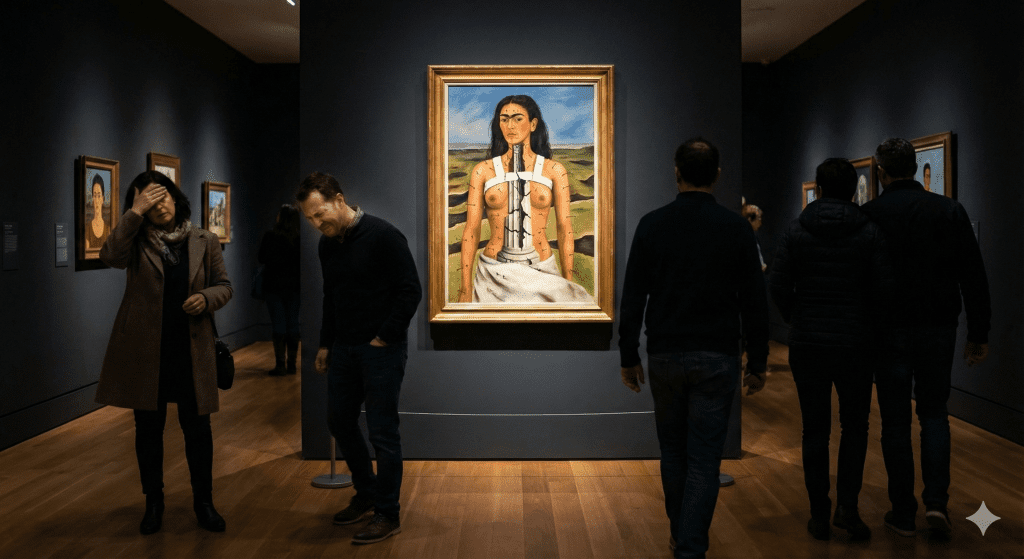

The painting measures just 15 by 12 inches, oil on masonite, intimate enough to hold in your hands. Kahlo depicts herself nude from the waist up against a cracked, ravine-scarred landscape. Her torso is split vertically from chin to pelvis, the skin peeled back to reveal a shattered Ionic column replacing her spine. The column is fractured in multiple places, barely holding together. A steel orthopedic corset cinches around her body, the only thing preventing complete collapse.

Fifty-four nails pierce her skin. Art historian Katy Hessel counted them for a BBC Radio 3 broadcast: they penetrate her face, neck, shoulders, arms, chest, and one leg. The largest nail drives directly into her heart. White tears, crystalline and precise, fall from her eyes. Her expression remains stoic, almost defiant, even as her body breaks apart.

The background offers no comfort. The earth itself appears earthquake-damaged, fissured with dark cracks that mirror the split in her body. She stands completely alone. No monkeys, no parrots, no Diego Rivera hovering in her thoughts. This is isolation rendered absolute.

The Medical Reality Behind The Broken Column

In 1925, eighteen-year-old Kahlo was riding a wooden bus when it collided with a streetcar. A metal handrail impaled her through the pelvis, fracturing her spine in three places, shattering her collarbone, breaking eleven bones in her right leg, crushing her right foot, and dislocating her shoulder. Doctors didn’t expect her to survive.

She survived. What followed was a lifetime of medical intervention: more than thirty surgeries, months in full-body plaster casts, years in orthopedic corsets, and ultimately the amputation of her right leg below the knee in 1953, one year before her death. The Broken Column documents this reality with clinical precision.

By 1944, when Kahlo painted this work, her doctors had recommended she transition from plaster casts to a steel corset for daily wear. The brace depicted in the painting is one she actually used. It survives today in Casa Azul, displayed alongside the painted corsets she decorated to make her medical equipment bearable. Furthermore, the painting coincided with another spinal surgery, one of many attempts to correct damage that could never truly be corrected.

The Artistic Lineage of Pain

Art historians connect The Broken Column to the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, depicted throughout Renaissance painting. Sebastian was a Roman soldier discovered to be Christian, tied to a tree, and used for archery practice. Artists from Botticelli to El Greco painted his arrow-pierced body with an odd combination of agony and ecstasy. He survived the arrows only to be beaten to death later.

Kahlo secularizes this martyrdom. The nails replace arrows. The corset replaces the tree. Consequently, the suffering has no divine purpose, no redemptive arc, no promise of sainthood. This is simply a body that has been broken and continues breaking. The comparison elevates Kahlo’s pain to the level of classical tragedy while simultaneously stripping away the religious consolation that made Sebastian’s torture meaningful.

Desmond O’Neill, a physician writing for the British Medical Journal, praised Kahlo’s ability to portray what medicine struggles to measure: the lived experience of chronic pain. “We lack the ability to grasp or express it,” he wrote. “Frida Kahlo is the exception.” The painting functions as both art and clinical documentation, a visual record of what X-rays and surgical reports cannot convey.

The Triptych of Suffering: 1944-1946

The Broken Column belongs to what some scholars call Kahlo’s spiritual triptych of pain, three paintings created during her medical and emotional nadir. Understanding the sequence illuminates each individual work.

The Broken Column (1944) establishes the baseline: a body held together by external support, pierced but standing, weeping but defiant.

Without Hope (1945) depicts the aftermath of a failed vertebrae fusion surgery. Kahlo lies in bed beneath a wooden frame, force-fed a funnel of meat, skulls, fish, and viscera. The painting documents her loss of appetite and the torturous feeding regimen doctors imposed. The sun and moon appear simultaneously in the sky, suggesting time has lost meaning during endless bedridden days.

Tree of Hope, Keep Firm (1946) concludes the sequence after what Kahlo called “the big operation.” She paints herself as two figures: one lying on a hospital gurney, back exposed with fresh surgical wounds; another sitting upright in a red Tehuana dress, holding a back brace she no longer needs and a flag reading “Árbol de la esperanza, mantente firme” (Tree of hope, keep firm). The second Frida watches over the first, a guardian self promising survival.

Viewed together, these three paintings trace a narrative arc from endurance through despair to fragile hope. The Broken Column functions as the opening statement, the declaration of what must be survived.

What Kahlo Chose to Reveal

Nudity in The Broken Column serves strategic purpose. Kahlo’s famous Tehuana dresses, the elaborate traditional costumes she wore publicly, functioned partly to conceal her back brace and damaged leg. The clothing became her brand, her armor, her construction of a public self that transcended disability.

Stripping away that armor for this painting constitutes a radical choice. She presents her body without the protective layer of cultural identity, without the distraction of jewelry and braids and pre-Columbian ornament. Furthermore, the steel corset that usually hides beneath fabric now becomes the visible infrastructure keeping her upright. What was private becomes clinical evidence.

The candor extends to her expression. Despite the tears, despite the nails, her gaze remains direct and level. She looks at the viewer without pleading, without self-pity, without the performative suffering that characterized much religious art depicting martyrs. This is documentation, not supplication.

Where to See The Broken Column

The painting resides permanently at the Museo Dolores Olmedo in Xochimilco, a neighborhood in southern Mexico City accessible by the Tren Ligero light rail. The museum occupies a seventeenth-century hacienda surrounded by gardens where hairless Xoloitzcuintli dogs and peacocks roam freely. Businesswoman Dolores Olmedo assembled the world’s largest private collection of Kahlo paintings, and The Broken Column is among its most significant holdings.

The Olmedo offers advantages over the more famous Casa Azul. Crowds are smaller. The setting is more contemplative. Additionally, the collection includes twenty-five Kahlo paintings and numerous drawings, allowing visitors to trace her artistic development across decades rather than seeing a few works in domestic context.

Plan to spend at least three hours. The museum closes Mondays. Photography is permitted in most areas. The hacienda grounds merit exploration independent of the collection, and the Xochimilco neighborhood provides access to the famous floating gardens and trajinera boat rides if you want to extend your visit.

What Sophisticated People Say About The Broken Column

Collector conversations about this painting benefit from these observations:

On the column symbolism: “The Ionic column references classical architecture, civilization’s foundational structures. By placing a crumbling column inside her body, Kahlo suggests that what we consider permanent, whether buildings or bodies, eventually fails. The personal becomes architectural.”

On the landscape: “The cracked earth mirrors the split in her torso. An earthquake fractures landscape the way her accident fractured her body. Kahlo extends her interior damage onto the external world, refusing to separate self from environment.”

On isolation: “Unlike most Kahlo self-portraits, The Broken Column includes no animals, no Diego, no symbolic companions. Chronic pain is depicted as fundamentally isolating. No one else can occupy that landscape with her.”

On the medical gaze: “Physicians use this painting in medical education to help students understand what pain feels like to patients. The work transcends art history to function as clinical literature.”

The Painting That Refuses Comfort

The Broken Column by Frida Kahlo offers no resolution. The column cannot be repaired. The nails cannot be removed. The corset cannot come off without the body collapsing. Unlike paintings that document her relationship with Diego Rivera, this work admits no external source of support or torment. The damage is internal, structural, permanent.

That refusal to comfort makes the painting difficult to commodify, despite its endless reproduction. The image on a tote bag loses its power because context disappears. Seen at actual scale, in person, at the Olmedo, the work retains its capacity to make viewers physically uncomfortable. Your body tenses. You become aware of your own spine.

Kahlo painted approximately 200 works during her lifetime. Many are beautiful. Some are politically charged. A few are genuinely disturbing. The Broken Column belongs to a small subset that function as testimony, as evidence, as records of experience that language cannot adequately convey. Standing before it, you understand something about human endurance that no verbal description provides.

The next time you see The Broken Column on merchandise, remember what it actually depicts: a woman who transformed unbearable pain into art that outlasted her body. The nails, the column, the corset, the tears, all survive on a small masonite panel in a hacienda in Xochimilco, waiting for visitors willing to look without flinching.

Stay Connected with Social Life Magazine

- Contact Social Life Magazine for editorial inquiries

- Experience Polo Hamptons — where culture meets sport

- Subscribe to Our Newsletter for insider access

- Print Subscription — join the conversation

- Support Independent Journalism