The dormitory hallway at Sherborne School stretched endlessly in both directions. Chris Martin, thirteen years old, walked with an awkward bounce in his step he couldn’t seem to control. A group of boys blocked the corridor ahead, their eyes already fixed on him. “There goes the gay one,” one of them called out. The others laughed.

Martin’s chest tightened. He’d grown up in the evangelical Belmont Chapel near Exeter, singing psalms with his parents every Sunday. The message had been clear: if he was gay, he was “completely f***ed for all eternity.” So every time he walked a little funny or bounced a little too much, the fear coiled tighter. He wasn’t just terrified of those boys in the hallway. He was terrified of himself.

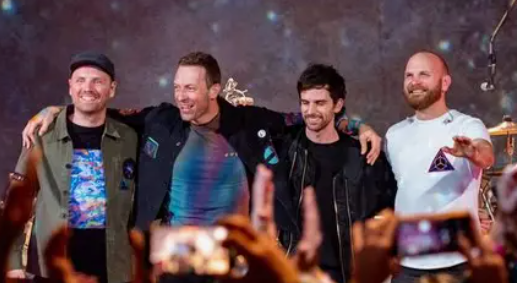

Three decades later, Chris Martin’s net worth sits at approximately $170 million. His band Coldplay has sold 160 million records worldwide. Their Music of the Spheres World Tour just grossed $1.52 billion and sold 13.1 million tickets, making it the most-attended concert tour in history.

However, somewhere inside the man filling Wembley Stadium for ten consecutive nights, that terrified boy still walks down a boarding school hallway, trying not to bounce.

The Wound: When God and Classmates Both Seemed to Judge You

Christopher Anthony John Martin was born March 2, 1977, in Exeter, Devon, to a family that represented comfortable English respectability. His father Anthony was a chartered accountant who served as a magistrate. His grandfather had been Sheriff and Mayor of Exeter. The family owned Martin’s Caravans, a motorhome business founded in 1929 that would sell for £8.8 million in 1999.

His mother Alison, originally from Zimbabwe, taught music. Their eight-acre property near Whitestone featured a horse paddock and tennis court. Meanwhile, the Martin children attended the evangelical Belmont Chapel.

Young Chris absorbed two things in that household: a profound love of music from his mother, and a paralyzing fear of damnation from his faith. At thirteen, he was sent to Sherborne School, the private boarding institution in Dorset where his religious anxieties would collide with adolescent cruelty.

“When I went to boarding school I walked a bit funny and I bounced a bit,” Martin told Rolling Stone decades later. “And I was also very homophobic because I was like, ‘If I’m gay, I’m completely f***ed for eternity.'” The classmates were relentless. “For a few years, they would very much say, ‘You’re definitely gay,’ in quite a full-on manner, quite aggressively.”

He later described those years as causing “terrible turmoil.” The boy who would eventually write “Fix You” and “Yellow” spent his formative adolescence convinced he might be fundamentally broken. His sexuality, his walk, his sensitivity, his very self all seemed like evidence of wrongness that could doom him forever.

The Chip: How Self-Doubt Became a Superpower

Martin emerged from Sherborne with his soul intact but rewired. The constant questioning had become internalized, transformed into something that looked like self-deprecation but functioned as rocket fuel.

“I don’t speak particularly well,” he’s said. “That’s one of the consequences of being extremely ugly.” He has called himself “not cool” and seemed genuinely unbothered by the admission. This isn’t false modesty. It’s the survival mechanism of someone who learned early that the safest response to criticism is to beat everyone to the punch.

He channeled everything into music. At Sherborne, he formed bands with names like The Rockin’ Honkies and served as president of the Sting fan club. In addition, he met Phil Harvey, who would become Coldplay’s manager and unofficial fifth member.

The chip on his shoulder grew sharper. Radiohead became his permission slip. “They were the band who gave me permission,” he’s explained. “I’m a public schoolboy from Devon and I’m not supposed to be in a band. Well, they proved I could.”

At University College London, studying Greek and Latin of all things, Martin found his bandmates: Jonny Buckland, Guy Berryman, and Will Champion. They formed Coldplay in 1996. From the beginning, Martin carried both the insecurity that made him doubt every note and the obsessive drive to make those notes perfect anyway.

The Rise: $170 Million Worth of Longing

The success arrived quickly and kept arriving. “Yellow” in 2000, written under a Welsh sky with Martin singing in his “worst Neil Young impression voice.” When Steve Jobs first heard it, he told them it was “shit” and they’d “never make it.” That cassette recording of twelve-year-old Chris playing keyboard at Exeter Cathedral School recently sold at auction for £840. The kid who couldn’t control his walk now controls stadiums.

Seven Grammy Awards followed. Nine Brit Awards. Ten studio albums. More than 160 million records sold, making Coldplay the most successful group of the 21st century.

The Music of the Spheres World Tour that concluded in September 2025 rewrote the record books. Total gross: $1.52 billion from 223 shows across 79 stadiums. Total attendance: 13.1 million tickets, the most in concert tour history. Their ten-night Wembley residency alone grossed $131.4 million. Consequently, Billboard ranked them the top touring group for four consecutive years.

Martin’s personal fortune now stands at approximately $170 million, though estimates range from $160 million to $202 million depending on the source. His bandmates each hold fortunes around $100 million. The band members donate 10% of all profits to charitable causes, a practice Martin began at age ten because his mother taught him to.

Yet the wound still shows. “I know I’m going to get shit for saying this,” he told an interviewer, “but yeah, I don’t want to be too happy. To write I have to feel slightly sorry for myself.” The songs keep pouring from the same source: that teenage sense of not quite belonging, of needing to prove something, of aching toward connection.

The Tell: Where the Original Hurt Still Shows

The evidence is everywhere if you know where to look.

In 2014, Martin’s marriage to Gwyneth Paltrow ended after a decade. He’d written “Fix You” for her after her father died. Subsequently, he descended into what he called a “year of depression.” He read Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning and the Persian poet Rumi. One poem, “The Guest House,” changed his life. It suggests inviting in dark thoughts rather than running from them.

The pattern repeated. In April 2025, mid-tour in Hong Kong, he posted a video on Instagram. “I’ve noticed that some people lately, including myself, are struggling a little bit with depression.” He shared his coping tools: freeform writing for twelve minutes then burning the paper, transcendental meditation, proprioception exercises. The vulnerability was vintage Martin.

“It’s difficult when you’re successful, to admit that you need help,” he’s said. “I think we boys, we men, are actually much weaker and softer than we like to think.”

The self-doubt has become its own kind of honesty. “People who write happy songs are often unhappy,” he once observed. “It’s helpful to have some arrogance with paranoia. If we were all paranoia, we’d never leave the house. If we were all arrogance, no one would want us to leave the house.”

The Malibu Compound: Building Safety 5,000 Miles from Sherborne

Chris Martin now owns at least five properties in Malibu’s Point Dume neighborhood. His latest acquisition: an $18.5 million compound with a 3.8-acre spread containing a Cape Cod-style main house plus two guesthouses offering eight bedrooms total. It sits right next door to another Martin property: a former church and 99-seat theater called the Malibu Playhouse that he purchased for $4.5 million in 2018.

The choice is telling. Point Dume offers beach access, mature trees, privacy walls of landscaping. It is the opposite of an English boarding school dormitory where anyone could walk in and call you names. The homes feature Pacific views, outdoor amphitheaters, tennis courts. Space to breathe. Room to be whoever you want to be.

He keeps buying properties in the area like someone building a fortress. Or perhaps like someone finally creating the safe space he never had as a boy.

The Garwood Residence, a $14 million waterfront home he’d shared with Paltrow, was razed entirely. In its place, Martin is constructing something new: a 5,500-square-foot two-story home with a tennis court, swimming pool, and private outdoor amphitheater. He’s quite literally building himself a stage at home.

The Paradox: Success Doesn’t Erase Childhood

In June 2025, reports emerged that Martin and his partner Dakota Johnson had split after eight years together. Another relationship ends. Another chapter closes. The pattern suggests that filling stadiums and bank accounts doesn’t necessarily fill the space that was carved out in a Dorset dormitory.

But here is what Chris Martin has built with his $170 million and his 160 million records: permission. Permission to walk however you walk. Permission to feel terrified and keep going anyway. Permission to write songs about longing even when you’ve achieved everything society says you should want.

Years ago, Martin ran into one of his former Sherborne bullies while accompanied by Gwyneth Paltrow. “He was a bully who always said I wouldn’t make anything of myself,” Martin recalled. “I had great pleasure in asking what he was up to now. He wasn’t up to much. Then I turned around and said, ‘This is my wife Gwyneth.’ His face dropped.”

Sweet revenge, perhaps. But here’s the thing about revenge: it means you’re still playing by their rules. You’re still proving something to them.

The boy who walked funny filled Wembley Stadium ten nights in a row. He owns enough Malibu real estate to constitute a small village. He has $170 million and depression and a meditation practice and songs that make people cry in their cars. He is still, at 48, figuring out how to be okay with himself. Just like the rest of us.

* * *

For features and partnership inquiries, visit sociallifemagazine.com/contact. Discover Polo Hamptons events at polohamptons.com. Subscribe to our print edition or join our email list for insider access to Hamptons culture.

Related: Jon Bon Jovi Origin Story | Polo Hamptons 2025: What to Expect This Season