Here’s the fact that should stop you cold: that same painting sold in 1980 for $51,000. The appreciation represents a 107,155 percent return. Understanding Frida Kahlo facts isn’t art history trivia. It’s investment intelligence. Moreover, it’s cultural currency that separates the serious collector from the casual observer at every gallery opening from Basel to Coyoacán.

The Frida Kahlo Facts That Reframe Everything

Most people know the broad strokes. Mexican painter. Unibrow. Married Diego Rivera. Bus accident. But the sophisticated collector needs deeper knowledge. Consequently, let’s establish the essential facts about Frida Kahlo that matter in contemporary art circles.

Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico City. However, she frequently claimed 1910 as her birth year instead. This wasn’t confusion or vanity. Rather, it was strategic mythology-building. She wanted her origin tied to the Mexican Revolution, understanding instinctively that artists are remembered for their stories as much as their brushwork.

Her father, Guillermo Kahlo, was a German-Hungarian photographer who immigrated to Mexico. Her mother, Matilde Calderón, was of Spanish and indigenous Purépecha descent. This mixed heritage would become central to Kahlo’s artistic identity. Furthermore, it positioned her work at the intersection of European technique and Mexican folk tradition that collectors prize today.

The Accident That Created an Artist

At eighteen, Kahlo was preparing for medical school. She was brilliant, ambitious, and had no intention of becoming a painter. Then came September 17, 1925. A streetcar collided with the bus she was riding. A steel handrail impaled her through the pelvis. Her spine fractured in three places. Her collarbone, ribs, and right leg shattered. Subsequently, she would undergo more than 35 surgeries throughout her life.

During her year of recovery, bedridden in a full-body cast, Kahlo began painting. Her parents installed a special easel and mounted a mirror to the canopy of her bed. “I paint myself because I am so often alone,” she later explained, “and because I am the subject I know best.” This statement reveals the essential Frida Kahlo fact that collectors understand: her work was never about self-absorption. It was about radical self-examination as artistic method.

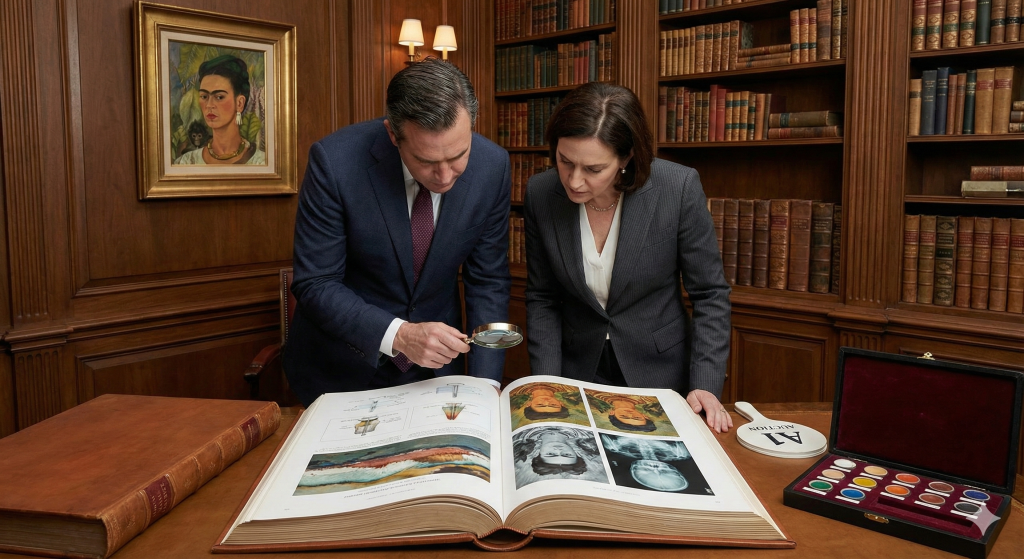

The bed itself became a recurring motif. Indeed, the $54.7 million painting depicts Kahlo asleep on a floating bed, a skeleton wrapped in dynamite hovering above her. Sotheby’s confirmed that Kahlo actually slept with a papier-mâché skeleton in her canopy. The line between her life and art dissolved entirely.

Diego Rivera and the Power Dynamics of Art World Marriages

In 1929, Kahlo married Diego Rivera, already Mexico’s most celebrated muralist. He was 42. She was 22. Her mother called the union “the marriage between an elephant and a dove.” Nevertheless, the relationship would prove central to both artists’ legacies, though in ways neither anticipated.

Rivera was famous. Kahlo was not. He painted massive public murals. She painted small, intensely personal canvases. During her lifetime, she was often introduced as Diego Rivera’s wife. Yet today, her auction records dwarf his. Her museum draws 25,000 visitors monthly. The Casa Azul has become one of Mexico City’s most-visited cultural sites, while Rivera’s murals, though magnificent, don’t command the same devotional tourism.

Their relationship was famously turbulent. Both had affairs. They divorced in 1939, remarried in 1940. Kahlo’s painting The Two Fridas, completed during their separation, shows two versions of herself: one loved, one betrayed, their hearts connected by a single artery. Understanding this biographical context enriches collector appreciation. Additionally, it provides the conversational depth that serious art people expect.

Facts About Frida Kahlo’s Artistic Method

Kahlo produced approximately 200 paintings during her career. Of these, 55 were self-portraits. This ratio is significant. She wasn’t simply painting what she saw in the mirror. Rather, she was constructing an iconography of self that would prove remarkably prescient for contemporary identity-focused art.

Her palette drew from Mexican folk art traditions: bold reds, vibrant yellows, the cobalt blue that would later define Casa Azul. She incorporated pre-Columbian symbols, Catholic imagery, and fantastical elements that earned comparisons to Surrealism. However, Kahlo rejected the Surrealist label entirely. “I never painted dreams,” she stated. “I painted my own reality.”

This distinction matters for collectors. Surrealism prioritized the unconscious and the irrational. Kahlo’s work, while dreamlike in appearance, was rooted in specific lived experience: her physical pain, her miscarriages, her complicated heritage, her political convictions. Consequently, her paintings function as both autobiography and cultural document.

The Tehuana Dress as Strategic Branding

Kahlo’s distinctive appearance was entirely intentional. The flowing Tehuana dresses, the elaborate flower crowns, the joined eyebrows she emphasized rather than plucked: each element communicated something specific. The Tehuana dress signified matriarchal indigenous culture. The pre-Columbian jewelry asserted Mexican identity over European influence. Even her disability became part of the visual narrative, hidden beneath long skirts that concealed the leg withered by childhood polio.

For contemporary artists and collectors interested in personal branding and identity construction, Kahlo offers a masterclass. She understood nearly a century ago what social media has made obvious: image and art are inseparable. Furthermore, authenticity and strategic presentation aren’t contradictions. They’re essential collaborators.

The Market Reality: Frida Kahlo Facts for Investors

Mexico declared Kahlo’s works part of the national cultural heritage in 1984. This designation prohibited their export from the country. As a result, paintings that remain in private hands outside Mexico command extraordinary premiums. Scarcity drives value. Additionally, comprehensive retrospectives are rare because major works cannot travel.

The recent Sotheby’s sale demonstrated this dynamic perfectly. El sueño (La cama) had been in private hands since 1980, rarely exhibited publicly. The consignor, later identified as the estate of Selma Ertegun, had purchased it for $51,000. Forty-five years later, it sold for $54.7 million. This represents not just appreciation but a fundamental shift in how the market values women artists, Latin American artists, and artists whose work speaks to contemporary identity politics.

Previously, Kahlo’s 1949 painting Diego y yo held her auction record at $34.9 million, set in 2021. That sale also broke records for Latin American art. The pattern suggests sustained momentum rather than a speculative bubble. Museums and serious collectors continue competing for the rare Kahlo works that become available.

Where to Experience Kahlo’s World

The Museo Frida Kahlo, known as Casa Azul for its cobalt blue exterior walls, remains the essential pilgrimage. Located in Coyoacán, Mexico City, this house museum is where Kahlo was born, lived with Diego Rivera, and died in 1954. Indeed, her ashes remain inside, kept in a pre-Columbian urn in the bedroom where she painted her final works.

The museum draws approximately 25,000 visitors monthly. Advance booking is mandatory. Slots sell out weeks ahead, particularly for preferred morning times. The serious cultural traveler books the 8am private tour before crowds overwhelm the intimate spaces. Subsequently, they combine the visit with the nearby Anahuacalli Museum, also established by Rivera, which is included with the Casa Azul admission.

What strikes visitors most isn’t any single painting. Rather, it’s the totality: Kahlo’s wheelchair positioned before an unfinished Stalin portrait, her paints still arranged on the palette, the mirror mounted above her bed that enabled the self-portraits. The house looks much as it did in 1951. Therefore, visitors experience not just an artist’s work but her actual life circumstances.

The Upcoming Exhibitions Collectors Should Know

In January 2026, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, debuts Frida: The Making of an Icon, curated by Mari Carmen Ramírez. This major exhibition features more than 30 works by Kahlo alongside 120 pieces by artists she influenced across five generations. The show examines how Kahlo transformed from a relatively unknown painter at her death to the global phenomenon she is today.

After Houston, the exhibition travels to Tate Modern in London, running from June 25, 2026, through January 3, 2027. Notably, this will be one of the few opportunities to see significant Kahlo works outside Mexico in a museum context. The MFAH collaborated with Museo Frida Kahlo to secure archival materials rarely available for public viewing.

For collectors and culture-forward travelers, these exhibitions represent must-attend events. The Houston opening aligns with the annual Texas cultural calendar, while the Tate presentation offers European collectors a rare opportunity. Plan accordingly.

The Cultural Capital of Frida Kahlo Knowledge

Understanding Frida Kahlo facts confers specific social advantages within art world circles. At gallery openings, auction previews, and collector dinners, conversation inevitably turns to questions of value, authenticity, and cultural significance. Kahlo sits at the intersection of multiple contemporary concerns: female representation in art history, Latin American cultural heritage, disability and the body, identity politics, and the relationship between artist biography and market value.

The term “Fridamania” emerged in the 1990s to describe her unprecedented popular appeal. Her face appears on merchandise globally, from tote bags to refrigerator magnets. Yet this commercialization hasn’t diminished her artistic standing. If anything, it has reinforced her status as one of art history’s most recognizable figures, comparable only to Van Gogh, Picasso, and Warhol in mainstream visibility.

For the serious collector building a significant collection, Kahlo represents both an aspirational acquisition and a conceptual touchstone. Even if actual Kahlo works remain beyond reach, familiarity with her oeuvre and influence enriches engagement with contemporary artists who reference her. Additionally, such knowledge demonstrates the cultural sophistication that distinguishes substantial collectors from mere purchasers of decorative objects.

Why Frida Kahlo Matters Now

The $54.7 million sale arrived during a turbulent moment for the art market. Galleries have shuttered. Auction volumes have contracted. Yet Kahlo’s price soared beyond estimates, suggesting that truly significant works by historically important artists remain immune to broader market corrections.

Furthermore, the sale coincided with renewed institutional attention to women artists and artists from outside the traditional Western European canon. The Tate and MFAH exhibitions represent major museum commitment to reassessing Kahlo’s influence. Consequently, prices may continue rising as institutional validation reinforces collector demand.

The essential Frida Kahlo facts add up to this: she transformed personal suffering into universal art. She constructed an iconic identity that anticipated contemporary personal branding by decades. She created work that speaks simultaneously to Mexican heritage and global audiences. And she achieved posthumous recognition that exceeded anything she experienced during her lifetime.

At the art fairs and collector gatherings where cultural capital matters, this knowledge translates directly into social positioning. Understanding Kahlo isn’t optional for the serious collector. It’s essential fluency in the language of contemporary art discourse.

Stay Connected with Social Life Magazine

- Contact Social Life Magazine for editorial inquiries

- Experience Polo Hamptons — where culture meets sport

- Subscribe to Our Newsletter for insider access

- Print Subscription — join the conversation

- Support Independent Journalism