A College Student Broke the Music Industry. Wall Street Rebuilt It.

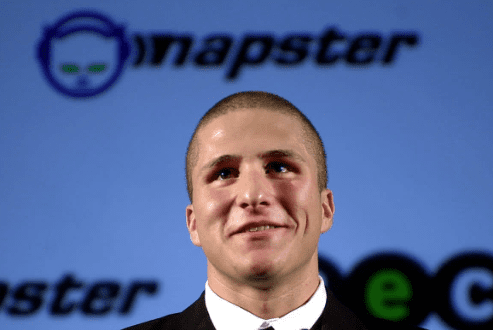

In June 1999, Shawn Fanning launched Napster from his Northeastern University dorm room. Within eighteen months, 80 million registered users were downloading music for free. U.S. recorded music revenues, which had peaked at $14.5 billion in 1999, would plummet to $7.7 billion by 2009. The 90s copyright wars destroyed the old music economy entirely. However, from that destruction emerged something nobody predicted: a new asset class that attracted over $20 billion in investment capital since 2019. The journey from Napster to streaming didn’t just change how people listen to music. It created a financial instrument that pension funds, private equity firms, and family offices now compete to own.

What Napster Actually Destroyed

The conventional narrative says Napster killed the music industry. That’s wrong. Napster killed a specific business model, the one where labels charged $15 for a CD containing two good songs and ten filler tracks. As music journalist Dan McManus noted at the time, Napster was “the revenge of the single.” Consumers had been overcharged for decades, and the moment technology offered an alternative, they abandoned the old system overnight.

Furthermore, the revenue collapse wasn’t caused entirely by piracy. Industry analysis from Rolling Stone shows that a significant portion of late-90s CD revenue came from catalog reissues, as consumers replaced cassette collections with CDs. That replacement cycle was always going to end. Napster accelerated a decline that was structurally inevitable. Nevertheless, the speed of the collapse caught everyone off guard.

The Copyright Wars Nobody Won

The Recording Industry Association of America responded to Napster with lawsuits. The RIAA sued Napster directly, and the Ninth Circuit Court upheld a ruling that forced the service to shut down in July 2001. Metallica and Dr. Dre filed their own suits. However, victory in court did not equal victory in the market. After Napster fell, decentralized alternatives, Kazaa, LimeWire, Gnutella, and BitTorrent, emerged to fill the void. Each was harder to sue because each was harder to shut down.

The RIAA then took the controversial step of suing individual file sharers. Between 2003 and 2008, the organization filed approximately 35,000 lawsuits against consumers. Harvard Business Review criticized the strategy as both ineffective and damaging to the industry’s reputation. A single mother in Minnesota was ordered to pay $222,000 for sharing 24 songs. The legal victories did nothing to reverse the revenue decline. By 2010, when LimeWire was finally shut down, the industry had lost half its revenue and much of its public goodwill.

The iTunes Compromise

The turning point came in 2003, when Steve Jobs convinced the major labels to sell songs through the iTunes Music Store at $0.99 per track. Jobs understood something the labels didn’t: convenience could compete with free. iTunes proved that consumers would pay for music if the experience was simple enough. In its first week, the store sold one million songs. By 2008, iTunes was the largest music retailer in the United States, surpassing Walmart.

Yet downloads were still ownership-based, and many users continued sharing purchased files. The model that would truly solve the piracy problem hadn’t arrived yet. That required a conceptual shift from ownership to access. In 2008, Spotify launched in Sweden with exactly that proposition: unlimited music for a monthly fee.

The Streaming Revolution and Its 90s Roots

Spotify’s model worked because it addressed the core behavior that Napster had revealed. People didn’t want to steal music. They wanted unlimited, instant access to all music. Napster proved the demand. Spotify built the legal framework to supply it. By 2025, streaming accounted for over 80% of recorded music revenue. McKinsey research confirmed that streaming revenues had effectively replaced the CD economy, though the distribution of those revenues remained contentious.

For 90s artists, streaming created a second economic life for their catalogs. Songs that had been purchased once on CD now generated ongoing royalty income with every play. Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas Is You,” released in 1994, reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 for the first time in 2019 thanks to streaming. The song now generates approximately $3 million per year, a revenue stream that didn’t exist when it was recorded.

How Copyright Wars Created an Asset Class

The most consequential outcome of the Napster era wasn’t technological. It was financial. Once streaming established predictable, recurring revenue from music catalogs, Wall Street noticed. Songs became assets with measurable cash flows, similar to real estate or bonds. Consequently, a new class of buyers emerged: investment funds dedicated to acquiring music catalogs.

Since 2019, at least $20.4 billion has poured into music rights acquisitions, according to research from the World Intellectual Property Organization. BlackRock, Blackstone, Apollo Global Management, and KKR have all entered the space. In 2025 alone, Chord Music Partners raised between $2 billion and $4 billion from pension funds and family offices. Warner Music and Bain Capital launched a $1.2 billion joint venture specifically for catalog acquisitions.

The 90s Catalogs Driving the Boom

The irony is rich. The same 90s catalogs that Napster nearly destroyed are now among the most valuable assets in the music investment market. Queen’s catalog sold to Sony for approximately $1.27 billion in 2024, the largest music acquisition in history. Bob Dylan’s songwriting catalog went to Universal for $300 to $400 million. Britney Spears sold her catalog to Primary Wave for approximately $200 million in February 2026. Justin Bieber and Katy Perry each sold their catalogs for around $200 million.

For financial advisors, catalog valuations typically range from 6x to 25x annual net publisher’s share (NPS). Nostalgic, evergreen catalogs command premium multiples because streaming data proves their listening patterns are stable and growing. A 90s hit with consistent streaming numbers is, in financial terms, a performing asset with low correlation to economic cycles. WIPO research confirms that music rights offer portfolio diversification benefits because consumption patterns don’t track traditional market movements.

The Winners of the Copyright Wars

The artists who understood ownership during the 90s are the biggest winners of the streaming and catalog boom. Jay-Z owns both his masters and publishing rights, making his music catalog worth an estimated $100 million before considering his other assets. Taylor Swift re-acquired her first six albums’ masters in 2025, creating one of the most valuable catalogs in modern music. These artists control assets that compound in value as streaming grows.

In contrast, artists who signed away their rights in the 90s are selling those rights now at prices that would have been unimaginable when Napster launched. The catalog boom represents a second chance for many 90s artists to monetize their work, even if the terms are less favorable than if they had retained ownership from the beginning.

What Comes Next: AI, Sync, and the New Copyright Frontier

The copyright wars haven’t ended. They’ve evolved. AI music generation, exemplified by companies like Suno (which raised $250 million in 2025 at a $2.45 billion valuation despite facing major copyright lawsuits), represents the next existential threat to music rights holders. Napster was sold in March 2025 to Infinite Reality for $207 million, then shut down its streaming service entirely on January 1, 2026, pivoting to an AI music platform. The brand that started the first copyright war may now be ground zero for the next one.

Meanwhile, sync licensing, the placement of songs in film, television, advertising, and social media, has become a major revenue driver that barely existed in the Napster era. TikTok alone has revived dozens of 90s songs by introducing them to Gen Z audiences, driving streaming numbers and catalog valuations higher. The copyright infrastructure that the 90s wars forced the industry to build is now generating revenue streams that the artists of that era could never have anticipated.

From Napster’s dorm room to today’s billion-dollar catalog funds, the 90s copyright wars reshaped the entire economics of music. The artists who survived the transition with their ownership intact are building generational wealth. The investment institutions that recognized music as an asset class are deploying capital at record levels. And the fans who downloaded songs for free in 1999 are now paying $10.99 per month to stream them legally. Nobody predicted this outcome. Everyone is profiting from it.

Related Reading: 90s Music Icons Net Worth 2026: The Biggest Stars of the Decade | The 90s Invented Modern Fame. Nobody Was Prepared.

Want to feature your brand alongside stories like this? Contact Social Life Magazine about partnership opportunities. Join us at Polo Hamptons this summer. Subscribe to the print edition or join our email list for exclusive content. Support independent luxury journalism with a $5 contribution.