On February 10, 2026, Britney Spears sold her entire music catalog to Primary Wave for approximately $200 million. Within hours, every major outlet had the headline. But the real story is not that Britney sold. The real story is who else already has, what they got, and what the pattern reveals about how 90s fame is being monetized in an era the artists who built it never imagined.

The music catalog market has exploded into a multi-billion-dollar asset class. Investment firms, private equity funds, and legacy music publishers are competing to acquire the rights to songs that defined a generation. And the 90s — the last decade where physical album sales, massive touring, and cultural ubiquity converged — sits at the center of the market.

The economics are straightforward. A catalog generates income from streaming royalties, sync licensing for film and television, radio airplay, and merchandise. When an artist sells, the buyer is purchasing future cash flow. The price is typically calculated as a multiple of net annual earnings — anywhere from 10x to 25x depending on the catalog’s streaming trajectory, cultural relevance, and licensing potential. In 2026, industry valuations typically range from 6x to 15x annual earnings for most catalogs, with legendary artists commanding premium multiples that can push far higher.

For aging icons, the calculus is simple. A catalog that earns $8 million annually might sell for $160 million today. Wait five years, and streaming growth could push the price higher. Or a cultural shift could depress it. Selling now locks in generational wealth. Holding is a bet that the asset appreciates faster than the money would if invested elsewhere.

Most of them are selling.

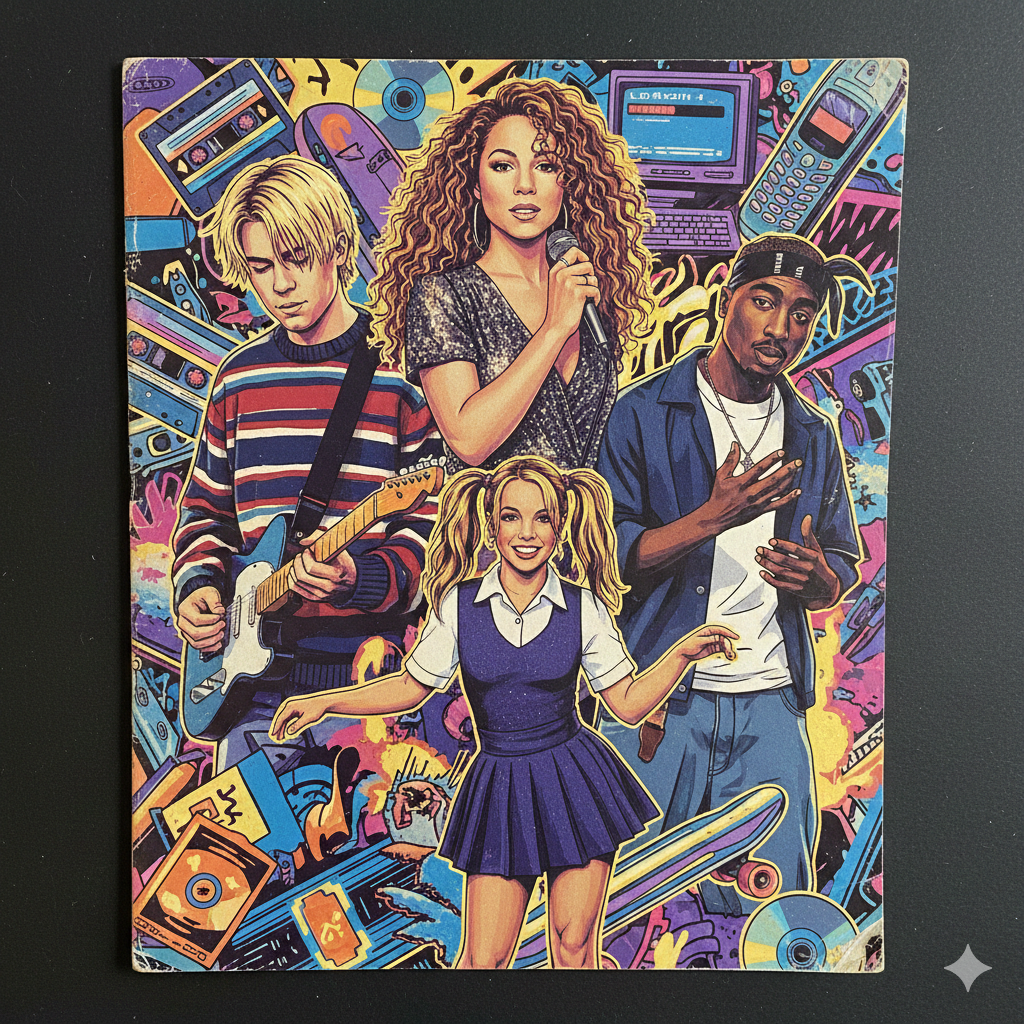

The 90s Catalog Scoreboard

Here is the roster of major 90s-era artists who have sold all or significant portions of their music catalogs, listed by reported deal value. This is not every deal — many close without public disclosure — but it is the most comprehensive accounting available.

Bruce Springsteen sold his entire catalog — masters and publishing — to Sony Music for approximately $500 million in 2021. It remains one of the largest single-artist 90s music catalog sales in history.

Bob Dylan sold his publishing catalog to Universal Music for an estimated $300 million in 2020, then sold his master recordings to Sony for approximately $200 million in 2022. Combined proceeds exceed $400 million.

Sting sold his solo and Police catalog to Universal Music for a reported $250 million in 2022.

Justin Bieber sold 100% of his catalog to Hipgnosis for approximately $200 million in 2023, making him one of the youngest major catalog sellers in history.

Britney Spears sold her entire catalog to Primary Wave for approximately $200 million in February 2026. The deal was signed December 30, 2025. It is the defining financial event of her post-conservatorship life.

Neil Young sold 50% of his career catalog to Hipgnosis for an estimated $150 million in 2021.

Red Hot Chili Peppers

Sold their publishing catalog to Hipgnosis for more than $140 million in 2021. The band is reportedly seeking approximately $350 million for their recorded-music masters separately.

Shakira sold 100% of her catalog to Hipgnosis in 2021 for an undisclosed sum.

Stevie Nicks sold 80% of her publishing to Primary Wave for approximately $100 million in 2020.

Kurt Cobain / Nirvana — Courtney Love sold 50% of Cobain’s share of the Nirvana publishing catalog to Primary Wave for a reported $50 million in 2006. This was the deal that launched Primary Wave’s entire business model.

Whitney Houston — Primary Wave acquired a 50% stake in the Houston estate in 2019 for a reported $7 million. Through aggressive marketing, sync placements, and the 2022 biopic I Wanna Dance with Somebody, the estate now generates roughly $8 million annually — up from $1.5 million at the time of purchase.

Aerosmith sold their entire catalog plus memorabilia to Universal Music in 2022 for an undisclosed sum.

What Taylor Swift Did Instead

Taylor Swift did not sell. She re-recorded. When Scooter Braun acquired her first six albums’ masters for $300 million via the Big Machine Records label sale in 2019 — without her consent — Swift re-recorded every album to create new masters she controlled. In May 2025, she bought back the originals from Shamrock Capital for approximately $360 million. She now owns both versions. She is the only artist in modern history to pull it off. That option was never available to Britney Spears under a conservatorship.

The Primary Wave Play

The company that just wrote Britney her $200 million check is not a record label. Primary Wave is a music publishing and IP management firm founded in 2006 by Larry Mestel, a former executive at Island Records and Virgin Records. Its first acquisition was 50% of Kurt Cobain’s share of the Nirvana publishing catalog, purchased from Courtney Love for a reported $50 million.

That single deal defined the company’s model: buy catalogs from iconic artists, then aggressively market, license, and revitalize them to increase their value. Primary Wave does not sit on catalogs and collect checks. It runs social media campaigns, pitches sync placements, produces biopics, and creates holidays. Smokey Robinson now has an official holiday, courtesy of Primary Wave’s marketing team and a deal with American Greetings.

The Whitney Houston example

Primary Wave bought a 50% stake in the Houston estate in 2019 for a reported $7 million. At the time, the estate generated about $1.5 million annually. Primary Wave commissioned a Kygo remix of “Higher Love” that became a streaming and sync hit, averaging 48.5 million streams per quarter. They co-produced the 2022 biopic I Wanna Dance with Somebody. Houston’s catalog saw over 2.2 billion streams in 2023, a 25% increase year over year. The estate now earns roughly $8 million per year.

That is the playbook for Britney. Primary Wave already owns catalogs from Cobain, Houston, Bob Marley, Prince, Stevie Nicks, James Brown, and Ray Charles. Adding Britney Spears gives them the defining pop voice of the late 90s and early 2000s — right as a Jon M. Chu-directed biopic enters production at Universal.

A catalog earning $10 million per year at a 20x multiple sells for $200 million. But if the buyer can grow that income to $15 million through sync deals, biopics, and streaming campaigns, the catalog’s internal value jumps to $300 million. The buyer’s profit is the delta between what they paid and what the revitalized catalog is worth. This is not music. This is private equity with better soundtracks.

Why the 90s Are the Sweet Spot for Catalog Sales

Not all decades are created equal in the catalog market. The 90s occupy an ideal position for several reasons.

First, cultural reach. The 90s produced the last generation of truly universal pop stars. Before algorithmic fragmentation split audiences into a thousand micro-niches, a Britney Spears or a Nirvana could dominate across demographics. Those songs are embedded in the collective memory of everyone between 35 and 55 — the demographic with the highest disposable income and the strongest nostalgia reflex.

Second, streaming economics. Catalogs from the 60s and 70s are being streamed, but at lower rates than 90s music because the listeners are older and less digitally active. Catalogs from the 2010s have high streaming numbers but face the risk of cultural obsolescence. The 90s sit in the goldilocks zone: old enough to be nostalgic, young enough to stream.

Third, sync demand. Advertising agencies and film studios use 90s music constantly because it triggers instant emotional recognition. The opening notes of “…Baby One More Time” or “Smells Like Teen Spirit” do more brand work in three seconds than a thirty-second voiceover. Sync licenses for iconic 90s tracks can command six figures per placement.

Fourth, the artists are still alive (mostly), which means branding opportunities, reunion tours, and documentary content that dead catalogs cannot generate on their own.

The 90s Catalog Sellers vs. the Catalog Keepers

Among the 15 90s icons we profile in this series, a clear divide is emerging. On one side: artists who are cashing out. On the other: artists who built ownership structures that make selling unnecessary.

Jay-Z has not sold. He does not need to. His wealth — estimated at $2.5 billion — comes from equity stakes in companies like Armand de Brignac, D’Ussé, and Tidal, not from music royalties. His catalog is a legacy asset, not an income dependency. Beyoncé has not sold either. She owns her masters outright, runs Parkwood Entertainment, and generates enough from touring and brand deals that catalog income is supplemental.

Dr. Dre has not sold his music catalog, though his primary wealth event was the $3 billion Apple acquisition of Beats Electronics in 2014. Eminem has not sold, and as the best-selling rapper of all time with a catalog that continues to perform strongly on streaming platforms, he is in no rush.

The sellers tend to share a profile

Artists who need liquidity, artists whose peak earning years are behind them, and artists (or estates) who lack the infrastructure to monetize their catalogs independently. Britney falls into a unique category — an artist whose conservatorship prevented her from building the business infrastructure that artists like Beyoncé and Jay-Z constructed during the same period.

There is also a less quantifiable factor. For Britney, selling the catalog severs her last operational connection to an industry that, by her own account, nearly destroyed her. She no longer needs to record, tour, promote, or interact with the music business in any capacity. The $200 million is not just wealth. It is freedom — the kind of freedom that was taken from her for 13 years.

That makes her deal fundamentally different from a Bruce Springsteen or a Bob Dylan selling at the tail end of a voluntarily managed career. The conservatorship money trail explains why Britney had so much less to work with when she finally regained control. The catalog sale is the corrective. It is the largest single wealth event of her life, and it was entirely her choice.

What Comes Next for 90s Music Catalog Sales

More 90s icons will sell. The Red Hot Chili Peppers are reportedly seeking $350 million for their recorded masters, separate from the $140 million publishing deal they already closed. Reunion tours from the Spice Girls or *NSYNC could either raise catalog valuations by proving continued demand or trigger sales by creating a valuation peak. The Diddy legal situation could force a fire sale of assets that would reshape catalog pricing for hip-hop catalogs broadly.

The deeper trend is structural. Music catalogs are becoming a legitimate alternative asset class, sitting alongside real estate, private equity, and fine art in the portfolios of institutional investors. Brookfield committed $1.7 billion to Primary Wave’s acquisition fund. Warner Music and Bain Capital launched a joint venture with $1.2 billion earmarked for catalog acquisitions. Concord’s catalog — which includes Beatles and Beyoncé compositions — was valued at $5.1 billion in a 2025 securitization deal.

For the artists

The decision to sell is ultimately about time preference. A dollar today versus a dollar (plus growth) tomorrow. For Britney Spears, a woman who lost 13 years of financial agency to a conservatorship, the preference for today was never really a question.

The 90s created the last generation of universally famous musicians. Now the decade’s music is being carved up and sold like beachfront property in a rising market. The artists who built business empires kept their catalogs. The artists the industry chewed up are selling them. Both groups are getting rich. Only one group gets to decide what happens to the songs next.

This article is part of Social Life Magazine’s 90s Music Icons Net Worth series, a 52-article investigation into how the decade that invented modern fame created — and destroyed — generational wealth.

Contact the Editors | Polo Hamptons 2026 | Subscribe to Print | Support Our Journalism

Related:

Britney Sells Catalog for $200M: What It Means for Her Net Worth

Britney Spears Net Worth 2026: Conservatorship to $200M Cash-Out