They Sold 200 Million Records. The Boys Got a Per Diem.

The Backstreet Boys are the best-selling boy band of all time with 130 million records sold. NSYNC moved another 70 million. Combined touring revenue exceeded $2 billion. The members of those groups, the faces on the posters, the voices on the tracks, the bodies doing the choreography, received a fraction of what they generated for the machine that owned them.

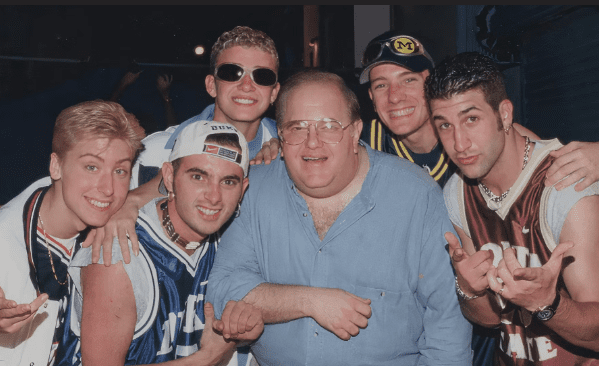

The boy band economy of the 1990s was the most efficient wealth extraction system the music industry ever built. One man sat at the center of it. His name was Lou Pearlman. And the story of what he did is not just a music industry scandal. It is a case study in what happens when talent has no leverage and capital has no oversight.

How Lou Pearlman Built the Machine

Lou Pearlman was not a music executive. He was a businessman from Flushing, New York, whose primary venture was an airship rental company. Most of the blimps crashed. Insurance proceeds from those crashes funded his pivot into music. He placed an ad in the Orlando Sentinel in 1992 calling for teenage boys to audition for a new vocal group. From several hundred respondents, he assembled what would become the Backstreet Boys.

Pearlman structured the contracts so that he was paid as manager, producer, and a sixth member of the group. That meant he received one-sixth of the band’s own income on top of his management and production fees. It was triple-dipping at industrial scale.

After the Backstreet Boys became global stars, Pearlman did something that would define the era. He told a writer for The New Yorker: “Where there’s McDonald’s, there’s Burger King. Where there’s Coke, there’s Pepsi. Where there’s Backstreet Boys, there’s going to be someone else. Someone’s going to have it. Why not us?” So he created NSYNC as his own competition. Same playbook, same contract structure, same exploitation.

$300,000 for Gold Records

The Backstreet Boys’ member Brian Littrell was the first to hire a lawyer to understand why the group had received only $300,000 total after selling millions of records and touring globally. The answer was in the contract they signed as teenagers. Pearlman and his entities had extracted nearly everything.

NSYNC’s situation was equally stark. Lance Bass has publicly stated that at the peak of their fame, selling out arenas worldwide, the group members received $35 per day as a per diem. Their self-titled debut had sold 10 million copies. Chris Kirkpatrick has described opening his first real paycheck after that milestone and finding barely four figures inside.

Both groups eventually sued Pearlman. The Backstreet Boys filed first. NSYNC followed. Aaron Carter, who was 14 at the time, filed his own lawsuit in 2002 alleging that Pearlman cheated him out of hundreds of thousands of dollars. The suits were settled. Pearlman was bought out of the contracts. But the damage, both financial and psychological, had been done.

The $1 Billion Ponzi Scheme Behind the Music

Pearlman’s exploitation of the boy bands was not even his primary crime. In 2006, investigators discovered that he had been running what was then the longest Ponzi scheme in American history, defrauding investors of more than $1 billion through entities called Trans Continental Airlines Inc. and TransCon Records. The companies existed only on paper until the boy bands took off and gave them a veneer of legitimacy.

Pearlman used the bands as props to attract investors. He would bring potential marks to the studio where NSYNC or the Backstreet Boys were rehearsing. The fame was real. The financial infrastructure behind it was entirely fraudulent. He falsified FDIC, AIG, and Lloyd’s of London documents to win investor confidence. More than $300 million remains unrecovered.

He was arrested in Bali in 2007 after attempting to flee. Then pleaded guilty to conspiracy, money laundering, and making false statements during bankruptcy proceedings. He was sentenced to 25 years and died in federal custody in 2016 at age 62.

The Structural Problem Nobody Fixed

Pearlman was an extreme case, but the structural exploitation he practiced was common in the 90s music industry. Record labels routinely signed teenage artists to contracts that allocated 85 to 90 percent of revenue to the label and management while the performers received advances that functioned as loans against future earnings. If the album failed, the artist owed money. If it succeeded, the margins were so thin that even massive sales produced minimal income for the talent.

The boy band model amplified this dynamic by splitting already-thin artist royalties among four or five members while a single manager collected fees from every revenue stream. The math was brutal. A group selling 10 million albums might generate $100 million in revenue. After the label took its cut, the manager took his percentage, and the production costs were deducted, the five performers might split $2 million. Before taxes.

Justin Timberlake escaped this system by going solo, building a $250 million fortune through music, acting, and business ventures that he controlled. His trajectory is covered in our Reinvention Artists series. The other NSYNC members were not as fortunate. The Backstreet Boys continued touring and earning, but none of the members achieved the kind of wealth that their record sales would have justified under fair contracts.

What the Boy Band Economy Teaches About Wealth

The boy band economy is the dark mirror of every feel-good wealth story in the Pop Royalty tier. Mariah Carey kept her catalog. Jennifer Aniston demanded backend points. Victoria Beckham built a brand she owned. The boy band members signed contracts as children, trusted adults who exploited them, and spent years in litigation trying to recover what was rightfully theirs.

For anyone managing wealth, advising clients, or structuring deals, the lesson is worth repeating: ownership beats income. Leverage beats talent. And the person sitting across the table does not have your interests at heart unless the contract says so.

Netflix’s documentary Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam provides a detailed visual account of Pearlman’s operation. For the broader context of how 90s record deals functioned as instruments of exploitation, see our deep dive into the 90s record deal structure. The full 90s Music Icons rankings provide the complete picture.

Want to feature your brand alongside stories like this? Contact Social Life Magazine about partnership opportunities. Join us at Polo Hamptons this summer. Subscribe to the print edition or join our email list for exclusive content. Support independent luxury journalism with a $5 contribution.

Related: Spice Girls Net Worth 2026 | The One Song That Pays More Than Your Portfolio