Susan J. Barron

NYC artist Susan J. Barron tells the story of two veterans who walked into her show, “Depicting The Invisible,” with their service dogs. They approached a portrait featuring a handsome bearded man crouched with a dog. The phrase “We found each other” haloes his head, and he is surrounded by quotes that tell his story: a friend dying in his arms in Iraq; relentless, vivid nightmares; two suicide attempts; and a dog trained to comfort him and wake him up, saving him from his nightmares. The veterans were visibly affected, and told Barron, “this is a portrait of us.”

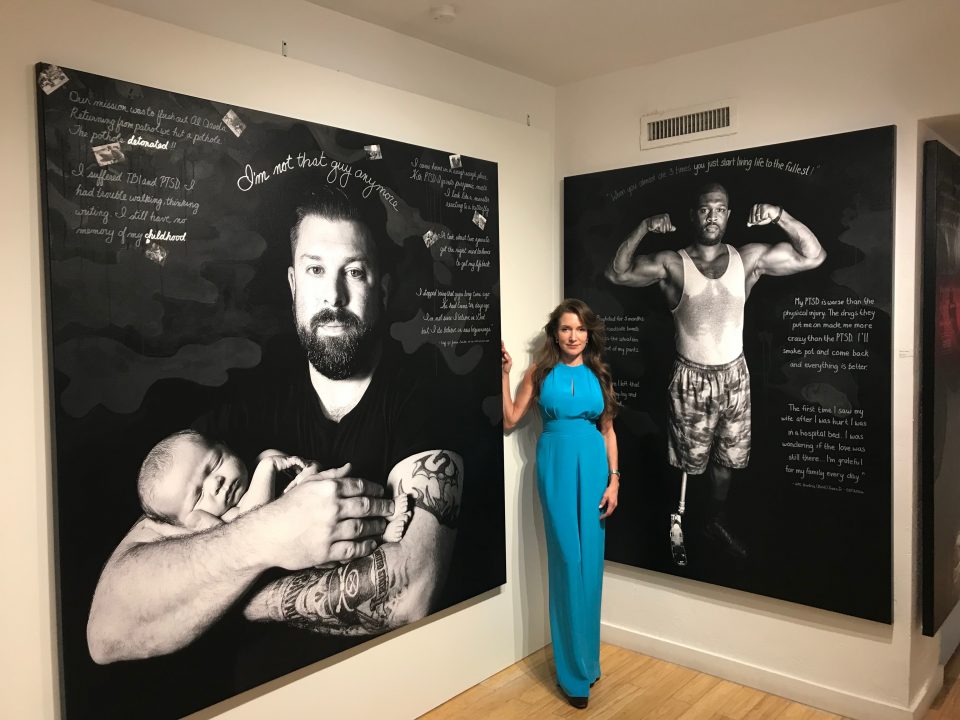

Depicting The Invisible

Barron created “Depicting The Invisible”, a portrait series of veterans suffering from PTSD, after learning that 22 US veterans commit suicide every day. “I was so shocked and appalled by the statistic,” she says, “I wanted to shine a light on the epidemic of PTSD and suicide, and I really felt that, if people could understand what’s going on, then they would be inspired to step up and make a difference.” Barron interviewed dozens of veterans, creating portraits to tell their stories. As the SoHo artist travels with her show, she has encountered “uncountable” veterans drawn to the images and the stories. Her goal, she says, is to make a human connection, and to give these veterans who often feel forgotten or invisible, a voice. “Every time the portrait series travels to a new city,” she says, “it magnifies their voices.”

Conversations

When she isn’t traveling, Barron is working on a different, lighter, project; “Conversations”. Here Barron uses imagery throughout the canon of art history to compose completely new works. These digital collages on canvas create a new visual dialogue that hyperlinks us through time and place. Her piece “Luncheon on the Grass,” for example, features Edouard Manet’s masterwork of a nude woman, but she’s sitting across from–in conversation with–an Alberto Vargas pin-up girl. “Two women painted by men over a century apart,” Barron explains, “The thought of what their conversation is, it’s just so delightful to me.”

SoHo

The “Conversations” canvases stand nine feet tall, and span styles and eras, and are all designed from Barron’s laptop, often at her home base of SoHo House in NYC. “During the day, there’s a whole collection of people working on their laptops,” she says, “some of them are writing plays or screenplays, or they’re writing the great American novel…and some of them are creating art.” Her perfect workday, she says, includes a stop at the Whitney Museum of American Art or a walk through the local galleries.

A Test

Just before the debut of “Depicting the Invisible,” Barron faced her biggest challenge. The mother of one of her subjects called her and told her that he had taken his life, or “fallen victim to the 22,” as Barron calls it. She was heartbroken. She had spent months talking to him and growing closer to him. Could she have known? Was it disrespectful to go through with the show? But, she says, other veterans reached out to her with sobering words of encouragement. She had to continue, they said, because Damon’s tragedy happens 22 times every day, and this is why you are doing this work; to stop it. She went through with the show, and visitors can still see Damon’s portrait, wreathed in quotes where he wrestles with his PTSD and the specter of suicide.

Inspiration

After DTI and Conversations, Barron is considering a portrait series of survivors of the September 11th attacks. She is in conversation with many victims’ families and is inspired by the incredible stories of those who lost a father, a spouse, a first responder. They are all heroes and she is inspired by the opportunity to tell the stories of those we might otherwise never hear. As she says, recounting the words of a former professor, “There are only so many pieces (of art) that you can make in your lifetime, so make them count.”